If there is anything symbolic of the warped, one-directional and ultimately, fruitless process of policy-making and implementation in Nigeria, it must be the federal government’s obsession with cassava bread, and its resolve, so to say, of chocking it down the throats of Nigerians whether they like it or not.

If there is anything symbolic of the warped, one-directional and ultimately, fruitless process of policy-making and implementation in Nigeria, it must be the federal government’s obsession with cassava bread, and its resolve, so to say, of chocking it down the throats of Nigerians whether they like it or not.

Cassava bread first gained prominence around 2003 when former president Olusegun Obasanjo endorsed loaves of cassava bread at a meeting of the Federal Executive Council. That the promoters would not choose to eat cassava bread was obvious even then, but government continued under the illusion that the rest of the country would drop everything else in favour of cassava bread.

Since that initial presentation over 10 years ago, cassava bread as a product has not caught on. Consumers of bread do not go out of their ways to specifically ask for cassava bread, as they would for say, wheat bread. Bakers too, have not bought into the cassava bread business because demand, assuming it exists, may not be worth their while or profitable. It should have been clear to the federal government that the policy had inherent weaknesses that needed redress.

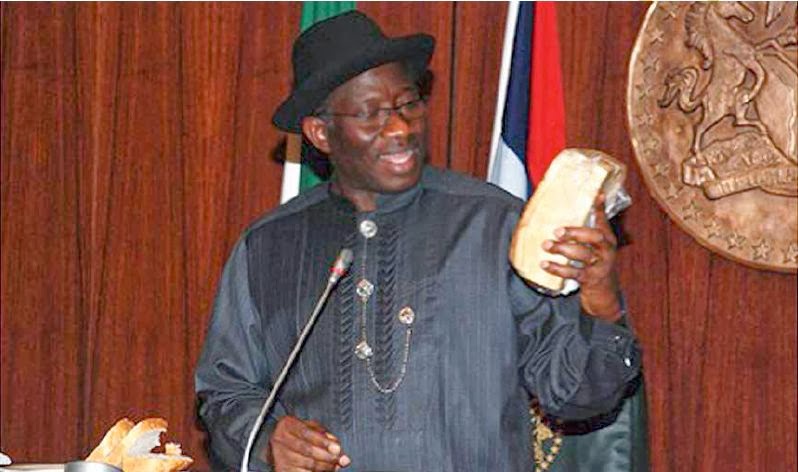

However, as is typical with policy-makers and public officials in Nigeria, it seems that the same stale cassava bread that Obasanjo presented to Nigerians in 2003 has been repacked and is now being re-presented again, this time by the Jonathan administration.

In a presidential villa that spends billions of naira annually on feeding, would cassava bread find space even in the waste bins? Who would imagine that the present tenants of the villa, who by their own admission, were born into and grew up in extreme poverty, would upset their sensitive palates with coarse cassava?

Knowing how government operates in Nigeria, there is probably a task force, unit or even desk in charge of the cassava bread project. It is also not inconceivable that it has a budget line in the ministry of agriculture with very fat funds released to the project annually. So to justify their existence, if not their relevance, they occasionally organise public activities to talk about the wonders of cassava bread and its nutritional values – while the real issues remain largely ignored.

To begin with, how many Nigerians really eat bread by choice? With growing poverty and incomes being constantly pared by inflation, bread, which should be a food for everyone is basically out of the reach of many Nigerians. For policy-makers ensconced in the luxury of government offices, this may be hard to believe, but the reality with many Nigerian families is that they do not have the capacity to make food purchases every day or two – which is the case with bread because it does not remain fresh for long. With tens of millions of people living on less than a dollar a day, how many people can afford bread, cassava or not?

But assuming that Nigerians want to eat bread and can afford to, why should government assume that people will opt for cassava bread, when there are varieties of breads, cakes and other confectionery to choose from? Even if cassava bread is supposed to be for people at the lower rungs of the economic ladder, it would an insult to their sensibilities to assume that they would not aspire to eat richly buttered and creamy wheat loaves.

Moreover, if one eats garri, eba, fufu and other meals derived from cassava daily, the last thing on that person’s mind would be another cassava based food.

The fundamental challenge of government’s cassava bread policy is the fact that it is not driven by economics. Profit-making is a powerful drive, and if there was a profit to be made somewhere along the line – from cassava farming and processing to the buying and selling of cassava flour and bread, government would not have needed to shout and preach over and over again about the virtues and desirability of cassava bread. Economic factors would have driven the process and made it a multi-billion naira industry long ago.

The cassava bread strategy also seriously under-estimates the obsession of Nigerians with preposterously expensive lifestyles: If Nigerians could import drinking water from Mars, we probably would. But since that isn’t feasible, we are doing the next most ludicrous thing: importing bottled Perrier water from France at huge cost. Even now, some newly affluent Nigerians will not be caught drinking anything else – such is our mania for all things foreign and expensive.

It was no surprise that the House of Representative rejected a bill seeking to make it mandatory to include cassava in the manufacture of all flour products in Nigeria. The fact is, unless the policy is overhauled, all those insisting on recycling stale ideas, if not stale cassava bread, should just let the matter be.