Coming into this place is one of the momentous times of my life. It is one of those moments when you lose control of yourself and refuse to be what is expected of you. In this place, you shun expectations; once you enter, you leave manhood outside and become a child with all curiosity intact, unsullied by adulthood.

This isn’t the first time I’ll be visiting here. And the feeling has always been the same.

Awe.

Trembling.

Wonder.

Anticipation.

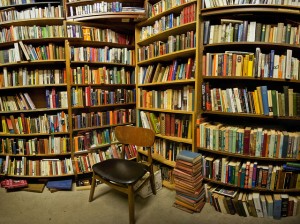

I am standing in the midst of books—shelves and shelves of brightly coloured, different sizes and various topics of books and books. It is even just enough to stand and gaze upon the volumes without making a choice—just standing and anticipating the possible transportation into uncharted experiences and beautiful ideas and imaginaries of the unknown. You can stand for hours in delicious anticipation. I have stood for hours, just moving about and browsing and picking and thumbing and buying and reading. It’s like window-shopping obscene jewelleries.

Why not get employment in a place like this? Why not make a job of reading? The thought crossed my mind, and not the first time. I asked those working there what it would take to seek employment there. They laughed at me. The laughter was rhetorical too: You must be joking or making fun of us! I told them my reason and they laughed the more: reading can’t be that significant. Yet they are wrong and I am right. Reading is life.

My earliest discovery of my capacity began with a book my mother gave me. It was Evbu My Love, by Helen Ovbiagele, one of the Pacesetter series on which most of my generation cut their literary teeth. Where she got it from is still a mystery, given that she wasn’t educated at all. Yet, she gave it to me (the instance of that transaction is even lost to memory). What isn’t lost is that I remember thumbing through the novel for pictures and images—my original Test for Relevance). The novel failed the test instantly and I dumped it. I didn’t start my intellectual life loving books. The early part of my secondary school evolution was a disaster; I applied the picture-image test religiously. The only textbook that consistently passed the test was Biology with all those drawings of animals and plants and our own biological secrets and evolution. Non-image texts made me suffer!

My earliest discovery of my capacity began with a book my mother gave me. It was Evbu My Love, by Helen Ovbiagele, one of the Pacesetter series on which most of my generation cut their literary teeth. Where she got it from is still a mystery, given that she wasn’t educated at all. Yet, she gave it to me (the instance of that transaction is even lost to memory). What isn’t lost is that I remember thumbing through the novel for pictures and images—my original Test for Relevance). The novel failed the test instantly and I dumped it. I didn’t start my intellectual life loving books. The early part of my secondary school evolution was a disaster; I applied the picture-image test religiously. The only textbook that consistently passed the test was Biology with all those drawings of animals and plants and our own biological secrets and evolution. Non-image texts made me suffer!

Back to Evbu My Love. I will never remember how I returned to the novel, but I did. It must have been boredom on one of those days. And it held the key to my literary epiphany. I haven’t looked back since that book. I went on to consume almost the entire title in that series, more than sixty in all. Then I turned to James Hadley Chase and the pennyworth thrillers. I remember prescribing one of the Chase thrillers for myself in the WAEC Literature recommendations. Ngugi, Achebe, Shakespeare, Osofisan and Hardy came in between. I could bear them all at this point because my original Test of Relevance had failed itself! I had actually been deceived by myself. But I recovered on time. Popular literature became my escape route from the drudgery of adolescence and the tyranny of my mother.

A not-so-funny instance readily comes to mind: As was usual, I was to do the cooking for the day. My mother took a semi-sabbatical immediately I reached adolescence and got the hang of the kitchen and other gruesome chores. That day’s task was a serious one. I was to prepare a pot of soup made up of fresh fish—one of our rare delicacies. But I also had a very interesting novel to finish and my younger brother had done his disappearing act away from work as usual. So, I made all the culinary preparations and got the soup successfully on the fire. That was the last I heard about it. I retreated into the room to continue reading (the topography of the face-me-I-face-you apartment, for those who are familiar with it, ensures that your ‘kitchen’ is just right in front of your room). What brought me back to ‘reality’ was the shout of neighbours lamenting the ‘burnt offering’. I didn’t even perceive the roast. My engrossment was total! My mother threw a tantrum that day. The ill-fated soup was irrecoverable. I was crestfallen but not remorseful. I shielded my novel and pointed accusing finger at my brother who always disappeared when there was serious task to be done. (And he had a way of miraculously reappearing when the food successfully get done!) My mother placed a heavy sanction on reading while cooking. It didn’t work but I didn’t offer up another burnt offering. I perfected a way of sneaking a view back up ‘reality’ any time I began reading.

And so I became a reader! And I have never looked back. I am sure my mother wasn’t surprised when I told her eventually I was going to make a career of reading and writing. I suspected she was a little disappointed though. She was expecting a plush employment in a bank or other corporate sites that yield immediate bonanza. Well, my first car came many many many years after stepping into academia. I haven’t still been able to get her a car, as she expects.

And so I became a reader! And I have never looked back. I am sure my mother wasn’t surprised when I told her eventually I was going to make a career of reading and writing. I suspected she was a little disappointed though. She was expecting a plush employment in a bank or other corporate sites that yield immediate bonanza. Well, my first car came many many many years after stepping into academia. I haven’t still been able to get her a car, as she expects.

But I have conquered many lands!

I have experienced many unknowns.

And that was the anticipation that throbbed my being any time I stepped into this place. I have my natural hideouts: Philosophy, History, Sociology and Political Science and other human sciences. But I have also gathered Adichie, Habila, Ngugi, Achebe, Soyinka, Umberto Eco; I have the Complete Works of Shakespeare, I have Montaigne and Santayana and Bacon and Emerson and Thoreau and all the rest. And never discountenance the role of popular literature in the constitution of reality: Grisham, Archer, Dan Brown, Ludlum, Baldacci, James Clavell (oh, the joy of the Shogun!), John Jakes and so on. I feed on Pope, Wordsworth, Ipadeola, Ofeimun, etc.

I even love Ikhide Ikheloa, except when he predicts the death of books!

Standing there on this particular day, I had the distinct revelation that Ikhide will eventually eat his prediction. Books won’t die. Metamorphose, yes. Even e-books can’t match the feel of holding Americanah or a Shogun. I haven’t properly lived a day without having fondled one or two of these treasures. What will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and desiccates his soul?

So I dedicate many hours regularly to coming here and renewing my pact with reality. I move round and fondle. I read blurbs and smile. I searched for and found myself right here. I am always drawn compulsively. I suspect the employees there think me insane because they see me regularly and they detect the love affair represented by growing number of purchases. My coming out essay might read somewhat like this: ‘I am bookish, mum’.

And on this day I had another epiphany: I am very certain now of how I want to die—right in a grave made of books. I didn’t begin my life in the midst of books, like Sartre, but I want to end it with them lining the walls and the floor of the six-feet tomb. That seems crazily ingenious to me. How else should one leave a world made better by books? What else guarantees a place in heaven?

_____________

Adeshina Afolayan teaches at the Department of Philosophy, University of Ibadan