by Deji Toye

In the play, A Dance of the Forests, a community prepares for a jubilee aptly called ‘The Gathering of the Tribe’. They have asked Forest Head to send them the resurrected spirits of a couple of their illustrious ancestors as fitting reminder of a great past. They are expecting empire-builders with the stature of Sundiata and Chaka (as the original Wole Soyinka text states), or Awolowo, Azikiwe and Fela (as director, Segun Adefila, renders it in the recent production of the play). Rather, the father of the forest approves a scheme by Aroni, the proverb-spurting sage of the forest, to send the celebrants two not exactly telegenic spirits from the same supposedly great period in African history—Dead man and his wife, pregnant Dead woman. In reality, these are manifestations of an injustice which had been perpetrated in the court of an empire builder of yore, Mata Kharibu. As we will see in a flashback scene later in the play, Warrior, Kharibu’s General and his expectant wife had been ‘sold down the river’ after the former refused to lead a new war to satisfy the emperor’s expansionist urges. Which refusal may be understandable, considering that the ostensible purpose of the latest war is to retrieve the trousseaus of the new queen, Madam Tortoise, from a neighbouring king from whom the emperor had only recently stolen his trophy wife.

In the play, A Dance of the Forests, a community prepares for a jubilee aptly called ‘The Gathering of the Tribe’. They have asked Forest Head to send them the resurrected spirits of a couple of their illustrious ancestors as fitting reminder of a great past. They are expecting empire-builders with the stature of Sundiata and Chaka (as the original Wole Soyinka text states), or Awolowo, Azikiwe and Fela (as director, Segun Adefila, renders it in the recent production of the play). Rather, the father of the forest approves a scheme by Aroni, the proverb-spurting sage of the forest, to send the celebrants two not exactly telegenic spirits from the same supposedly great period in African history—Dead man and his wife, pregnant Dead woman. In reality, these are manifestations of an injustice which had been perpetrated in the court of an empire builder of yore, Mata Kharibu. As we will see in a flashback scene later in the play, Warrior, Kharibu’s General and his expectant wife had been ‘sold down the river’ after the former refused to lead a new war to satisfy the emperor’s expansionist urges. Which refusal may be understandable, considering that the ostensible purpose of the latest war is to retrieve the trousseaus of the new queen, Madam Tortoise, from a neighbouring king from whom the emperor had only recently stolen his trophy wife.

But it is sufficient for now to note that these grumbling couple whose spirits still wander the forests many centuries later, seeking for justice and closure, are not the guests being expected by the local organising committee—“we asked for statesmen, they sent us executioners”. In a display of brinkmanship, a council member devices the re-commissioning of the lorry, Chimney of Ereko, whose notoriety for carnage both on and off the road has only recently led to its eventual retirement, a long overdue act of public good achieved so late due to the corruption of local officials. Chimney, it is, that is now commissioned to hurtle through the forests – smoke and sparks in tow – to smoke out the undesirable visitors. This, even at the risk of setting the woods on fire and disturbing the cosmic balance which makes the forest spirits part and parcel of communal life and the jubilee.

This play was written as an official commission for Nigeria’s independence in October 1960. After all, those who initially chose the script would appear to have reasoned, how better to celebrate a new nationhood than with a play with ‘dance’ in its title and an evocation of African legends in the lines of its poetry? At least, that was the plan until, as the account goes, perhaps an unusually attentive official sensed the suppressed snigger under the playwright’s seeming work of patriotic duty. Thus was the play chucked off the official programme, much like the two accusing spirits in the play.

There could be no better justification for a creative work with critical axe to grind. That very response from the officials of the newly independent nation has made rhetorical what could otherwise have been a genuine question, which is, why lay such heavy burden of introspection on a young nation in the tic of celebration? It appears the 26-year old playwright already noted the tendency for uncritical celebrations to dull the capacity for clear assessment of history and to sap the energy required for the crucial task of nation building. Therefore, the eve of independence was perhaps no time too soon to begin to reflect on how Africa which had produced the libraries and learning centres of Timbuktu, the technologies of the Ife and Igbo-Ukwu arts and the stone architecture of Great Zimbabwe, somehow, through internal weaknesses mostly its own, lapsed into a dark period that made it susceptible to the opportunistic infections of slave trade and colonialism.

There could be no better justification for a creative work with critical axe to grind. That very response from the officials of the newly independent nation has made rhetorical what could otherwise have been a genuine question, which is, why lay such heavy burden of introspection on a young nation in the tic of celebration? It appears the 26-year old playwright already noted the tendency for uncritical celebrations to dull the capacity for clear assessment of history and to sap the energy required for the crucial task of nation building. Therefore, the eve of independence was perhaps no time too soon to begin to reflect on how Africa which had produced the libraries and learning centres of Timbuktu, the technologies of the Ife and Igbo-Ukwu arts and the stone architecture of Great Zimbabwe, somehow, through internal weaknesses mostly its own, lapsed into a dark period that made it susceptible to the opportunistic infections of slave trade and colonialism.

And the answer is all there in the court of Mata Kharibu. Name it: an emperor who has reduced the constitutive power of state to the mundane pursuit of libidinal supremacy; a corrupt bureaucracy (the court Historian whose sole purpose is to cast and recast history in justification of the emperor’s latest whim; the court Physician hopelessly torn between his professional oath and self-preservation); or the even more corrupt business and middle classes with no sense of nationalism to match their economic or social ambitions (the local middleman in the global trade in slaves, ever ready to fund necessary inducement to war in order to produce sufficient stock for the next Middle Passage crossing). Even Madam Tortoise, that composite Jezebel-Delilah archetype, has managed to be reincarnated in the present where she still deploys her attributes to lay with, and as she desires, lay low both great and lowly alike (this character, in particular, is evidence, if any is needed, that Soyinka’s impatience with Nigerian ‘first ladies’ is nothing personal to Stella Obansanjo or Patience Jonathan, but a long-standing revulsion for the transgression of the slim claim of spousal privilege that often results in their overbearing intrusion in the public space).

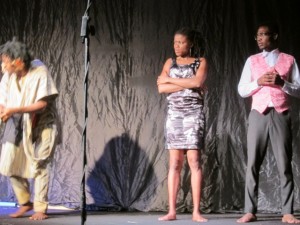

All these make Adefila’s directorial update essential to a production 54years later. Two productions have been commissioned for Soyinka’s 80th birthday this July. The bigger fair was the one directed by Tunde Awosanmi of University of Ibadan, in which an actual forest, close to the celebrant’s country home in Abeokuta, was turned into a theatre with the appropriate set and props to match. But for Lagos audiences who could not make the one-hour trip to that big event, Adefila’s production in the hall at Terra Kulture and the open-air concert stage at Freedom Park offered something even more in the spirit of the play— reducing the fair to its fitting dimension and punctuating the celebration with ruminative shocks now and then.

Firstly, Adefila’s discipline could produce a revue on the point of a pin. Then, as a director, he has that propensity to strip a script to its bare essence and recast it in a mould all his own. A director who pushes the directorial licence farther than most, for him, a constant Brechtian jolt of his audiences to see through the seductive entertainments of the show into their own shocking reality is almost an obligation. And to achieve this, that stand-up comic trick of ‘something happened on the way to the theatre’ is an artistic reality. To recount a personal experience, I was surprised when, sometime in 2006, I went to see a production of my play, The Botching of a Brute, with which I ought to have been more familiar than any other member of the audience, only to discover that Adefila had managed, without compromising the larger issues of the play, to draw it into the on-going intrigues over the ‘third term agenda’ of then President Obasanjo. The director’s message was as clear to me as any other person in that audience: this was not a play about a rebel leader in a distant African civil war, nor was it merely the play written for the radio in 1996, adapted to stage in 1999 and directed for the first time by Adefila himself four years before; this was a production for the times.

Firstly, Adefila’s discipline could produce a revue on the point of a pin. Then, as a director, he has that propensity to strip a script to its bare essence and recast it in a mould all his own. A director who pushes the directorial licence farther than most, for him, a constant Brechtian jolt of his audiences to see through the seductive entertainments of the show into their own shocking reality is almost an obligation. And to achieve this, that stand-up comic trick of ‘something happened on the way to the theatre’ is an artistic reality. To recount a personal experience, I was surprised when, sometime in 2006, I went to see a production of my play, The Botching of a Brute, with which I ought to have been more familiar than any other member of the audience, only to discover that Adefila had managed, without compromising the larger issues of the play, to draw it into the on-going intrigues over the ‘third term agenda’ of then President Obasanjo. The director’s message was as clear to me as any other person in that audience: this was not a play about a rebel leader in a distant African civil war, nor was it merely the play written for the radio in 1996, adapted to stage in 1999 and directed for the first time by Adefila himself four years before; this was a production for the times.

A similar message appears directed to audiences who saw Adefila’s three or so shows of A Dance of the Forest in mid July: you are not witnessing the court of a medieval African king as such, this is not just a play written for Nigeria’s independence in 1960, in fact, it is a 2014 production, this is a dance of Nigeria, of the Ekiti election, of Boko Haram and political brinkmanship, it is the life you are leading even now; deal with it! Which message could be lost easily if non-familiarity with Adefila’s theatre mixes with the notoriously complex plot of the play (see here for example a review by the linguist and writer, Kola Tubosun, which I think, in parts, misses some of the points).

However, in my view, one incongruous point in Adefila’s updating of that play is the naming of Fela among the venerated ancestors whom the celebrants would really welcome to their party. I take the view, which I have discussed with the director, that Fela is more in the character of the Warrior— the wandering, accusing spirit. For most of his life, Fela was not just a curse to the rulers, but also an embarrassment to the middle class (whom he accused of ‘colo-mentality’ and other misbehaviours similar to those displayed by Mata Kharibu’s courtiers). He was the bearer of truths about ourselves we would rather have buried away. Like the Warrior, he paid handsomely for it. And the middle class colluded in his ostracising, perhaps perceiving him as a betrayer (it was certainly difficult to reckon with Fela’s background and dismiss his as the ranting of some bitter member of the great unwashed). At least, that was the case until his posthumous resurrection almost as an international musical statesman. That resurrection itself symbolises a sort of return to haunt the conscience of the nation. It is not uncommon these days, to hear the rhetorical question: ‘didn’t Fela sing about it way back then?’

However, in my view, one incongruous point in Adefila’s updating of that play is the naming of Fela among the venerated ancestors whom the celebrants would really welcome to their party. I take the view, which I have discussed with the director, that Fela is more in the character of the Warrior— the wandering, accusing spirit. For most of his life, Fela was not just a curse to the rulers, but also an embarrassment to the middle class (whom he accused of ‘colo-mentality’ and other misbehaviours similar to those displayed by Mata Kharibu’s courtiers). He was the bearer of truths about ourselves we would rather have buried away. Like the Warrior, he paid handsomely for it. And the middle class colluded in his ostracising, perhaps perceiving him as a betrayer (it was certainly difficult to reckon with Fela’s background and dismiss his as the ranting of some bitter member of the great unwashed). At least, that was the case until his posthumous resurrection almost as an international musical statesman. That resurrection itself symbolises a sort of return to haunt the conscience of the nation. It is not uncommon these days, to hear the rhetorical question: ‘didn’t Fela sing about it way back then?’

Yet, there is little evidence to suggest that, if Fela really does re-appear today, he or his message would be better received than the last time. After all, the message of A Dance of the Forests continues to be lost in translation in the relevant quarters, including even in the academia. Only a couple of years ago, a certain professor granted an interview to one of the literary pages of a Nigerian newspaper, in which he, in essence, held Soyinka responsible for Nigeria’s current woes, ‘because of the curse he placed on the nation in that play he wrote for our independence’ or something to that effect.

Just for the notes, the play does end on a somewhat hopeful note. In the dance of the Half-child at the end of the play, the complaining spirits of the Dead couple are finally acknowledged and, under Forest Father’s direction, the pregnant woman is relieved of her centuries-old burden. The unborn child, which may well symbolise the stillborn or perpetually unborn great nationhood we ostensibly seek, is delivered at last. And here lies the key message of the play: in acknowledging the entirety of our past, and addressing its ugliness in particular, we may yet break the cycle of retrogression to which the nation is hostage. With some chance, we might receive this message which, just as the Dead couple of the play, will simply not go away (after all, as it turns out, this production manages to spoil the feast a second time, happening in the very year that the current government in Nigeria chose to celebrate Nigeria’s centenary). But in the end, this hopeful note is subject to our own learning ability. As the teaching Aroni would say after any one of his numerous adages in the play, ‘proverb to bone and silence’.

Just for the notes, the play does end on a somewhat hopeful note. In the dance of the Half-child at the end of the play, the complaining spirits of the Dead couple are finally acknowledged and, under Forest Father’s direction, the pregnant woman is relieved of her centuries-old burden. The unborn child, which may well symbolise the stillborn or perpetually unborn great nationhood we ostensibly seek, is delivered at last. And here lies the key message of the play: in acknowledging the entirety of our past, and addressing its ugliness in particular, we may yet break the cycle of retrogression to which the nation is hostage. With some chance, we might receive this message which, just as the Dead couple of the play, will simply not go away (after all, as it turns out, this production manages to spoil the feast a second time, happening in the very year that the current government in Nigeria chose to celebrate Nigeria’s centenary). But in the end, this hopeful note is subject to our own learning ability. As the teaching Aroni would say after any one of his numerous adages in the play, ‘proverb to bone and silence’.

________

Deji, lawyer and writer, sends this from Lagos.