A moment after I finished reading Unoma Azuah’s latest novel Edible Bones, the following lines from T.S. Eliot’s Little Gidding wafted into my mind: “What we call the beginning is often the end/And to make an end is to make a beginning/The end is where we start from…” But that will not be the starting point of my review of Unoma Azuah’s highly readable novel. Rather, I will commence by observing that, not since The Lonely Londoners has there been, in my own repertory of readings, such a rich exploration of exilic/émigré conditions and consequences as we find in Azuah’s book. Although the two books are remarkably different in regard to emplotment and language, it is quite easy to see that, in their engagement with the émigré condition, both books fit what Stephen Clingman has described as transnational fiction, a generic category that takes as its most defining and obvious character writers and writings that transcend national boundaries. Writers and writings in this category are plenty and there has developed a thriving critical industry around them; indeed, the term migrant literature or migration literature, which is an alternative nomenclature for transnational fiction, is now such an established commonplace in literary criticism that explicating its contours in some detail here may seem not only a platitude but also tangential to my purpose in this review.

A moment after I finished reading Unoma Azuah’s latest novel Edible Bones, the following lines from T.S. Eliot’s Little Gidding wafted into my mind: “What we call the beginning is often the end/And to make an end is to make a beginning/The end is where we start from…” But that will not be the starting point of my review of Unoma Azuah’s highly readable novel. Rather, I will commence by observing that, not since The Lonely Londoners has there been, in my own repertory of readings, such a rich exploration of exilic/émigré conditions and consequences as we find in Azuah’s book. Although the two books are remarkably different in regard to emplotment and language, it is quite easy to see that, in their engagement with the émigré condition, both books fit what Stephen Clingman has described as transnational fiction, a generic category that takes as its most defining and obvious character writers and writings that transcend national boundaries. Writers and writings in this category are plenty and there has developed a thriving critical industry around them; indeed, the term migrant literature or migration literature, which is an alternative nomenclature for transnational fiction, is now such an established commonplace in literary criticism that explicating its contours in some detail here may seem not only a platitude but also tangential to my purpose in this review.

For ease of comprehension, however, it should be helpful to remark that, since this is an age of intense migration, migration literature refers to all literary works that are written in an age of migration —or at least to those works that can be said to reflect upon migration. And this is precisely what both The Lonely Londoners and Edible Bones share in common—that is, they are both profound reflections on migrant subjects and migration in the present transnational world of commodity/human traffic and travels. But more important to my project in this review is the fact that the two books indicate the devastating impacts of migration on the subjects; in this regard, that devastation manifests most tellingly in the shape of disillusionment arising from dashed hopes and expectations. I shall have a bit more to say about this in the third paragraph of this brief review.

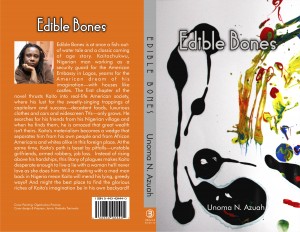

Edible Bones is the absorbing story of Kaito, a Nigerian and former employee of the American embassy in Nigeria who travels to the United States in search of the proverbial greener pastures. Starry-eyed, he arrives in God’s Own Country full of expectations. Armed with only a first degree, his plan is to find a good job, make money and live the American Dream. In a series of bizarre events and encounters—first with his friend’s former wife, April, and later with a receptionist, Beth, who offers him shelter in exchange for money and whose insatiable appetite for sex and drugs leaves him feeling exasperated—that made him to wonder if he has not lost his bearing, he is quickly awakened to the fact that life in America is not exactly the Eldorado that he has imagined it to be. Soon he finds himself in murkier waters and by the time he has been in America for three years—most of the time hiding from immigration officers and the police because he does not have the right papers and ID—he has not only been forced to put up with the degradation of working in all sorts of places and earning paltry wages under terrible conditions, he has also on three different occasions been involved with three different women who make his life quite miserable. They are the type of women whom, were he not in dire straits and desperate to escape ignominy, he would not have touched with a long pole. He later marries one of these women, out of necessity—to give him a chance to change his immigration status after being arrested and sent to jail for being in possession of a fake green card/ID and because he needs a shelter over his head. After his marriage to Jemina, perhaps the most overbearing of the three women, things appear to be looking up for him and he makes the decision to visit Nigeria with his wife. That return journey to Nigeria marks the beginning of what turns out to be a capitulation of sort as it brings him face to face with the stark futility of his effort to live the American dream; he has nothing to show for his three-year stay in the country he calls ‘freedom’, and his friends, the ones with whom he has shared the American Dream before he departs Nigeria, are better off in the same country he leaves three years before. Realizing how deep he has sunk in disgrace, he decides to make a new start in Nigeria, thus giving credence to the axiomatic truth of Eliot’s assertion that “What we call the beginning is often the end/And to make an end is to make a beginning/The end is where we start from…” Kaito’s release from jail and his marriage to Jemina which he hopes will mark the beginning of a fresh start is actually the end of his stay in America. His decision not to return to America with Jemina is the beginning of the fresh start he looks forward to in Lagos.

Edible Bones is not an unusual tale of migration and its consequences; such tales are a diurnal commonplace among migrants and in migration literature. The landscape of urban insecurity, homelessness, uncertainty and perennial fear which Azuah constructs is peopled by the usual cast of characters that has become the fare of migration literature. This cast of characters includes urchins, an underclass of migrants (mostly Blacks, Hispanics, Chinese, Arabs, Indians living in sordid condition) eking out a bare existence as petty thieves, shop lifters, con artists, drunks and drug addicts, small business owners, and, sometimes, fláneur, women desperate for a man to take them to bed, and, usually, a coterie of upper class Whites holding in disdain the immigrants in their country. Sometimes the landscape takes on the hue of a dystopia, with immigrants locked up in the fear of being surprised by a gunman in some dark alley or of having his/her meager possession stolen in some urban backwater where he/she is managing to eke out a miserable living. Power relations between immigrants and their hosts is almost always the most important catalyst for the conflict in such tales. Also, the experience of one migrant, as we see in the case of Kaito in Azuah’s book, provides a parallax view into the general experience of migrants at a particular point in time. Finally, there is no predictable pattern of denouement in such stories but there is frequently a pervasive mood of disenchantment or disillusionment arising, as I said before, from abject loss of hope, and it is usually at that moment of critical self-reflection that the immigrant becomes aware of how much he/she has lost in the whirlpool of migration. Several times in the narrative, Kaito arrives at that moment of disjuncture; and at such a moment of epiphanic self-consciousness he usually slips into a miasma of self-pity, but it is not until the end of the novel before this awareness of loss will become the stimulus for his decision to change the course of his life and to accept the need for a fresh start. This is where Edible Bones announces its departure from The Lonely Londoners; for while the protagonist, Moses Aloetta, in the latter novel appears to have settled comfortably into the quagmire of loss and disillusionment that characterize his life as an immigrant, Kaito in Edible Bones rejects out of hand this condition and charts an alternative course for himself. Obviously, this is the moral that Azuah wishes to impress on us.

However, there is an aspect of Azuah’s story that is not usual and that should engage our attention, even if briefly. I refer to the author’s courage to take on what is often regarded as a taboo subject, particularly in this part. Homophobia and homosexuality have not often been subjects for regular public debate in Nigeria; that is, until recently when the National Assembly called for a public hearing regarding a bill seeking to give constitutional recognition and legitimacy to same sex marriage. And to my mind, the only author in the Nigerian literary establishment that has given considerable attention to these issues is Jude Dibia, whose novel Walking With Shadows, has been acclaimed for its courage in this regard. In Azuah’s book, a case is made for homosexuality when Kaito arrives in America and finds, to his dismay, that men openly express admiration for other men, seeking to make them their sex partners. Later in jail, he comes to realize that contrary to standard universalist claims, homosexuality has a sociobiological explanation and that homosexuals are as much normal as any heterosexual being. Although he is at first repulsed by the idea and he regards homosexuals—including his self-appointed guardian in prison, Zulkibulu—as perverts, he gradually accepts the idea as plausible and homosexuals as one of the social variety of life. In a country like Nigeria where majority of the populace would flinch from having anything to do with gay and lesbian people, Azuah’s defense of queer sex is a courageous act indeed.

The final aspect of Azuah’s book that I wish to briefly touch on is the prose style or the lack of it. While emplotment and motivation are handled with a degree of self-consciousness, the author does not appear to be very keen on rendering her story in a prose of any particular elevation. In other words, the prose is as bland as it comes. Although this blandness does not detract from the other aspects of the narrative where the author handles her craft with a measure of assuredness (for instance, verisimilitude, the abundance of humour, the profusion of events, eccentric characters and so on), it is one’s considered opinion that sublimity of prose would have made the book a better work of art. It is a fast-paced fiction, and this, I suggest, is because the author was more interested in telling her story than in the kind of prose she has used in telling the story. I make this claim rather guardedly, aware that there are other possibilities in terms of how to view the matter.

Edible Bones is a useful addition to our literature and it is my hope that other readers have/will found/find something of value in it as I have done. Edible Bones breathes life, and Azuah makes that life real.

_______

Yomi Maren Ogunsanya studied Theatre Arts and Anthropology at the University of Ibadan. He currently lives and works in Ibadan, Nigeria.

I learnt new words: emplotment and parallax 😉 Well written!