“Is there anything to eat in this house this evening?” Barbara asked.

“There’s porridge,” I replied.

“Porridge is not food. Porridge is just something that I will drink with the main meal,” Barbara announced.

We were both confused on our definitions of porridge. She told me that porridge is made from corn or millet. From her description, I knew that she was talking about pap or custard. So, I showed her a sachet of custard that I had, and described how to prepare it. She confirmed it as porridge. Now, I know that if I go to a restaurant in Uganda and ask for porridge, I will get something in a cup. In Uganda, our porridge does not exist; their porridge is our custard. This brought to fore the difference in terms for different things and how cultural context could change the meaning of words. It also emphasizes the authoritarian nature of words. Who, for instance, said that porridge should be so-called, or that custard should be so-called? Are there inherent features in both that make them called such names?

Meet Barbara the teacher, my housemate at the Ebedi Residency. The way she talks, you will know she likes teaching. Her statements are spiced with “you know what?” “you understand?” as if to check that you are following. I learn that “Oliotia” and “Wasuzotia” mean “good morning” and “how was your night?” respectively. I learn that the structure of education in Uganda is different from Nigeria’s. They have seven years of primary education (P1-P7); then, six years of secondary school (four years of O’ Level) and (two years of A’ Level); then, three or five years of university depending on your course. Education is free from P1 up to Senior 6, it is the university that is competitive, which you have to pay for or fight for the few scholarships.

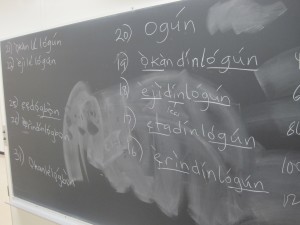

I also learn that up to a stage of primary education, the students are taught in local languages. We both taught students, most of them in classes between JSS1 and JSS 3. I asked the question: as black as… Expecting them to complete it, they looked at me with blank faces. Then, I translated it into Yoruba: o dúdú bíi… They all completed it: kóró isin. Easily, there’s relief on their faces. That was when it dawned on me, that they understood better in Yoruba, that they understood better with examples picked from their immediate environment. There are kóró isin trees all over Iseyin. From then, we had fun with the similes and metaphors. They threw me instances in Yoruba, many of them that I struggled to translate, many of them forms of abuses. Ó s’ojú bí ìwé ìròyìn: “Your face as broad as the pages of a newspaper”. Ó s’esè bí adìye tí n lo meeting: “Your legs like the legs of a chicken going to meeting”. Ojú e tóbi bí ojú òpòló tàbí òwìwí: “Look at your big eyes like a frog’s or an owl’s”. I have new questions on my mind: what harm would it do us to teach primary education in the local language of the community where the school is situated? Why do people feel that speaking Yoruba perfectly would lead to an imperfect knowledge of English? Why are our local languages tagged vernacular in most schools?

I also learn that up to a stage of primary education, the students are taught in local languages. We both taught students, most of them in classes between JSS1 and JSS 3. I asked the question: as black as… Expecting them to complete it, they looked at me with blank faces. Then, I translated it into Yoruba: o dúdú bíi… They all completed it: kóró isin. Easily, there’s relief on their faces. That was when it dawned on me, that they understood better in Yoruba, that they understood better with examples picked from their immediate environment. There are kóró isin trees all over Iseyin. From then, we had fun with the similes and metaphors. They threw me instances in Yoruba, many of them that I struggled to translate, many of them forms of abuses. Ó s’ojú bí ìwé ìròyìn: “Your face as broad as the pages of a newspaper”. Ó s’esè bí adìye tí n lo meeting: “Your legs like the legs of a chicken going to meeting”. Ojú e tóbi bí ojú òpòló tàbí òwìwí: “Look at your big eyes like a frog’s or an owl’s”. I have new questions on my mind: what harm would it do us to teach primary education in the local language of the community where the school is situated? Why do people feel that speaking Yoruba perfectly would lead to an imperfect knowledge of English? Why are our local languages tagged vernacular in most schools?

Barbara is a woman of many parts; writer, teacher, wife, mother, board member of the Ugandan Women Writers’ Association. Besides talking about writing and our countries, we talked about women issues. We read about Ugochukwu Onuchukwu, and wonder why women allow themselves to be blinded by love, even to the point of death. We wonder about generational differences between men and women; why is it that in the older generation (our parents’) there were lesser reported cases of spousal abuse leading to death unlike now. Barbara thinks that, maybe unlike before, many women are getting more empowered, as such becoming bigger sources of threats to men. More women also seem to stand up for their rights today. One thing remains same though, all these empowerment has not translated to women making choices to leave their marriages until they exit in death despite being financially empowered. Meet Barbara the feminist. She says that she is tired of explaining to people why she is interested in women matters. That if standing for women, makes her a feminist, then, so be it!

I learn more about Uganda, about its political terrain, past and present. I hear about Idi Amin, whom I watched those shocking movies of as a child. Well, I didn’t know Museveni had been a President for so long, for about 26 years. I learn that there was a treasured relationship between Museveni and Ghadaffi, that Ghadaffi built one of the most beautiful mosques in Uganda. I begin to think to myself: what does Museveni think of the death of his friend? Doesn’t the death of his friend make him have a rethink of his long-term rule as President? Doesn’t it make him begin to think that maybe it is time to train someone who would be “fit for President”? She tells me of the new strategy of civilians to get politicians to listen. She speaks of nodding disease, a disease that gets its name from the action of nodding and affects children. For a long time, the politicians were not giving it deserved attention, despite media coverage. Until some activists, took some children, with the disease to the Parliament. That was when they began to act. This made me think of Nigeria. While our representatives seat in the house and accrue to themselves unbelievable salaries; what do we do? We sit in our houses and whine. We seat in our online homes and rant. How about a protest where they are not allowed to leave the House until important bills like the Health and Social Security Bill for instance are passed into law. Maybe desperate situations call for desperate measures, for Uganda, and for Nigeria.

Then, we spoke about work ethic, in both countries. She is surprised that when it is about 9pm around here, one hardly find shops open. That before 9am you also find them closed. She says that is not the case in Uganda where stalls are open almost round the clock, especially during festivities. I am wondering, what about security? She confirms they have their security issues too, but people have learnt to live beyond it. This work ethic is also revealed in their schooling. Children do not leave school until around 5pm. She is surprised when I tell her that here, the average schools close around 2pm. She says that’s enjoyment. But I wonder what children, especially the really young ones would be doing till 5pm? On this, she thinks that the Ugandan system needs to learn from the Nigerian education system.

Our six weeks have long ended, memories of time spent with her, lessons about Uganda, lurk somewhere in the corners of my head. I wonder how you can learn so much from someone, about a country, in weeks.

___________

Temitayo Olofinlua, a writer, was recently at a retreat at the Ebedi’s Writer’s Residency at Iseyin, Nigeria. She’s also a co-manager of the Bookaholic Blog.