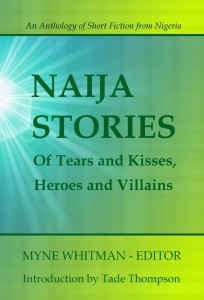

Naija Stories: Of Tears and Kisses, Heroes and Villains edited by Myne Whitman is a collection of thirty short stories by Nigerians about life in Nigeria except for one story, which plays in the Nigerian Diaspora. Apart from this shared element, the stories are very diverse.

Many, many topics

Two stories touched me the most. The first one is narrated from the perspective of a little girl. She herself does not really understand what is happening. However she knows that what daddy is doing to her is wrong. At the same time she remembers her teacher saying that “Daddies should always be obeyed”. What that teacher should have told her instead is that it’s ok to say no. In the end the girl blames herself, just as society often blames adult victims of rape for provoking the perpetrator. The second story is almost like a continuation, only that it is now a different daughter and a different father who doesn’t respect her rights. This time a father wants to marry off his daughter, who is still in primary school, to pay for his debts. The saddest bit about these two stories is that they are not just stories but reality for way too many children.

Many other stories also address very serious issues. One of these issues is the struggle of the people living in the Delta area, who suffer from pollution from oil refineries while the derived wealth does not benefit the majority of them. Other stories give a glance at the belief in divination, witchcraft and prophetic dreams, which can cause grave harm. E.g. a couple and their child are killed because a diviner declares that the unborn baby is an abomination. Though it is definitely true that some traditional believes must be condemned, this is also true for certain Christian practices. That’s why I am missing stories that are critical of Christianity on one hand and others that show positive aspects of the indigenous religions on the other hand. One author portrays a woman’s dream of travelling to England and shows how some people including this character would do almost anything to be able to leave Nigeria. It would have been nice to read also about people who made it abroad and then realised that they have to face many hardships that nobody had told them about before leaving. Another story stresses the importance of looking after your health, while yet another touches abortion. Many stories deal with the death of loved ones. Some of them die through violence, which shows that there is still a lot to do until Nigeria will be relatively safe from armed robbers and bomb attacks. Last but not least, several people die in car accidents. As roads and vehicles in Nigeria are usually in very poor condition, this danger cannot be overstressed.

Many other stories also address very serious issues. One of these issues is the struggle of the people living in the Delta area, who suffer from pollution from oil refineries while the derived wealth does not benefit the majority of them. Other stories give a glance at the belief in divination, witchcraft and prophetic dreams, which can cause grave harm. E.g. a couple and their child are killed because a diviner declares that the unborn baby is an abomination. Though it is definitely true that some traditional believes must be condemned, this is also true for certain Christian practices. That’s why I am missing stories that are critical of Christianity on one hand and others that show positive aspects of the indigenous religions on the other hand. One author portrays a woman’s dream of travelling to England and shows how some people including this character would do almost anything to be able to leave Nigeria. It would have been nice to read also about people who made it abroad and then realised that they have to face many hardships that nobody had told them about before leaving. Another story stresses the importance of looking after your health, while yet another touches abortion. Many stories deal with the death of loved ones. Some of them die through violence, which shows that there is still a lot to do until Nigeria will be relatively safe from armed robbers and bomb attacks. Last but not least, several people die in car accidents. As roads and vehicles in Nigeria are usually in very poor condition, this danger cannot be overstressed.

Apart from the more serious topics as the ones mentioned above, there are also everyday stories. A girl makes a first attempt at cooking but, as every beginning is hard, something goes wrong. In a different story a young man works up the courage to approach the girl he fancies, while a day dreamer mistakes his fantasies for reality. A pupil, who is being bullied, has to confront his biggest enemy and another teenager resists group pressure and follows his conscience instead. These story show that in many regards Nigeria is like any other country, with people who live their lives and the problems that they face.

More about Nigeria

About 500 languages are spoken in Nigeria. Thus, while the language of this anthology is English, it is infused with words from and quoted speech in Nigerian Pidgin English, Yoruba, Igbo, Efik and possibly other languages. Somebody who never has been to Nigeria should understand all stories but might puzzle at a few words. There is oyinbo which usually refers to white people and foreigners but sometimes is also used for Nigerians living abroad; abi can be added to a statement in order to question its truthfulness; oga addresses a boss or an otherwise important person; oriki is a name that praises positive traits of a person or their family; while an abiku is a child that is believed to be born and re-born only to die again and again at a very young age.

Most non-English words and sentences, including the ones just mentioned, are Yoruba. There are a few other ones, such as obodo, which in Igbo mean country, and amebo, an Efik word which is used to describe a person who likes to gossip. Most noticeably Hausa, which together with Yoruba and Igbo is one of the three largest languages of the country, seems to be completely absent (or at least so rare that I have not spotted a single word). The Nigerian languages represented appear to be a consequence of the ethnic background of the authors, which mostly bear Yoruba and Igbo names.

Just as in the case of the authors, the ethnicity of many characters can be deduced from their names. Moreover those names often reveal one or another detail about the circumstances of their birth. Hence we know that Taiwo is the first born of twins and Kehinde the second born. However, in opposition to the Western belief, Kehinde is regarded as the older of the two. She or he sends the junior sibling ahead to check out whether the world is good enough to be born into. As parents may be addressed by their children’s name, Kehinde and Taiwo’s parents are referred to by the author as Mama and Baba Ibeji, the parents of twins.

There are also some mentions of institutions that are particular to Nigeria. The National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) e.g. is a one-year-long service that is obligatory for all Nigerian graduates younger than 30. As part of their service they are sent to a region different from their own, which is supposed to foster unity. The service has been also criticised for exploiting these young people as cheap labour, putting them in danger and assigning them to jobs for which they are not qualified. Another presumably lowly paid job is that of the gate man. He is responsible for letting people and cars into compounds or entire neighbourhood and his presence is supposed to increase the security of the residents. Then there is MOPOL, which I had to look up myself and which stands for MObile POLice. Last but not least, the Nigerian currency is the Naira (N) and the sum of N 350,000 that is mentioned in one of the stories presently equals about $2,200 or £1,400. It should also be noted that the Liberation Army of the Niger Delta (LAND) is a fictive organisation modelled after the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND).

Laughter, tears and suspense

Now you might think that you are in for a very dry and boring read. However this is not the case. You probably will laugh out loudly, maybe even roll on the floor when reading about the clash between an upright mother and her unruly son. To her dismay, he turns up late at church with beer on his breath and, as the service carries, you can be sure that the son has ample chance to embarrass his mother again.

While reading other passages you should keep tissues close by. There is a grown-up daughter who remembers her late father by keeping a colouring book he meant to give to her shortly before he died. Another time two friends realise their feelings for each other. As they part ways due to life’s circumstances we are left with the sad impression that their love will not endure the distance unless they can keep it alive despite all odds. When, in a different story again, a mother dies and you realise that her son will never be able to make up with her, you might be reminded of a time when you yourself were wishing that you could turn back time and handle matters differently.

Suspense also does not come short in this anthology. You will wonder whether a young writer will be killed by members of a confraternity whom he had portrayed negatively in a newspaper article. You will fear for the life of teachers and students, when a school becomes the target of armed terrorists. Maybe you will hope for a rekindling of love between a man and his girlfriend who had been away to England for a long time. Or will you favour the new woman in his life?

Conclusion

I can only recommend this anthology. It contains fascinating stories about different aspects of life in Nigeria (and marginally in the Nigerian Diaspora as well). These stories offer entertainment, address important issues such as child abuse and teach us about a country that some readers might never have set foot on so far.

____________________________

Anja Choon is a PhD student in Field Linguistics at the School of Oriental and African Studies. She also works as a research assistant in the ICE Nigeria Project at the Westfälische Wilhems – Universität Münster. Currently she is looking forward to travelling to Nigeria for the tenth time.