___________________

First of all, congrats on your shortlist. Were you expecting it?

Thank you. It was a tough long list for the Nigeria Prize, one naturally is hopeful that the work will pass muster for the shortlist but really it was up to the judges.

Was there anything in your mind that could have prepared you for the announcement (of the longlist, and the eventual shortlist)?

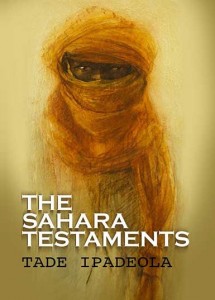

When I finished writing The Sahara Testaments, I sent it to a couple of friends within and outside the country. A good number of them felt the work had substance enough to stand on its own merit. My editors, Biyi Olusolape and Benson Eluma felt the same. The opinions of my friends who were literary scholars: Akin Adesokan, Wumi Raji, Amatoritsero Ede, Afam Akeh and Ian Duhig gave me some confidence that the work will travel.

Sahara Testaments is your third book (After A Time of Signs, and The Rain Fardel). When did you start writing it, what was the motivation, and how did you come about the name for the collection?

The book began assembling itself in my head circa 2003 but I didn’t begin actual writing of the book in its present form until 2009. I always wanted to write about African prehistory and geography. I think the main trigger was a visit to my office by Biyi Olusolape who after looking at my prior collections sort of threw the gauntlet for a more substantial work. Crossing the Sahara at noon en route a reading in Dehli was another trigger. Even from 36,000 feet in the air you can see the features of the Sahara because it is so hot that the clouds generally are thinner. It was after I started publishing the work in Next on Sunday that Professor Niyi Osundare read it and suggested including the human history of the Sahara. It couldn’t be a chronicle any longer, it became testamentary.

The book began assembling itself in my head circa 2003 but I didn’t begin actual writing of the book in its present form until 2009. I always wanted to write about African prehistory and geography. I think the main trigger was a visit to my office by Biyi Olusolape who after looking at my prior collections sort of threw the gauntlet for a more substantial work. Crossing the Sahara at noon en route a reading in Dehli was another trigger. Even from 36,000 feet in the air you can see the features of the Sahara because it is so hot that the clouds generally are thinner. It was after I started publishing the work in Next on Sunday that Professor Niyi Osundare read it and suggested including the human history of the Sahara. It couldn’t be a chronicle any longer, it became testamentary.

Before being shortlisted for the prize, what has been the response to the work from the number of public readings you’ve done?

Actually, I haven’t done much public reading from the work. I have published more in newspapers and literary supplements. The few public readings I did do in Ibadan, New Delhi and Johannesburg were very well received. I remember the reading at Stockholm also. These confirmed to me that I was on to something.

Your two earlier books were self-published, as I assume this one also is. How have you ensured quality, and how do you respond to critics of self-published work?

Indeed only my second book, The Rain Fardel was self published. The Sahara Testaments has been luckier in that it was actually published by Hornbill House of the Arts, a stable run by the poet Odia Ofeimun. Also, the electronic version of the book available on Kindle was published by Scribes Lane, a stable run by Molara Wood. There is an European edition in the works to be published by Khalam Editions. Some really great poets originally were self-published – Ezra Pound and Derek Walcott among them. It is not the ideal arrangement since a poet never has the time to engage the market the way it ought to be but in our peculiar circumstance, it cannot be avoided.

You are a lawyer by profession. When did you start writing, when did you start writing poetry, and who were/are your notable influences?

Actually, I wrote essays from when I was in secondary school and won a regional medal together with prize money of N50 in 1986, the year I became an undergraduate. In 1986, tuition fee at a Federal University for the academic year was N90 so you can say I part-underwrote my studies. Poetry I began writing in earnest by 1990. My biggest influences at the time were J.P Clark, Wole Soyinka, Niyi Osundare, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Yeats and Keats. Much later I discovered Heaney, Brodsky, Walcott, Kavanagh, Harry Garuba and Paul Muldoon. One of my lecturers, the late Sesan Ajayi was also a big influence. He spoke with seriousness when it came to literature. There was also a ferment in Ibadan circa ’96 – ’99 in which Lola Shoneyin, Lola Abioye and me were active.

I first met you in 2005 shortly before or during the publication of The Rain Fardel. How would you rate the development/evolution of your own poetic voice/craft since the publication of that collection. What changed, if any?

Stamina. Between The Rain Fardel and The Sahara Testaments, I learnt to stay with my subject and to pursue multiple possibilities as well. It must be the Walcott volumes. And the Osundare. Those two poets. I think the Pablo Neruda also. Neruda’s Canto General does have a looser quality to it than the works of the two poets I just mentioned. Yes, I remember reading Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate as well. He too taught me to stay with my subject. Apart from that, my voice has not changed much.

Around 2004/5 was also when the NLNG inaugurated the Nigerian Prize for Literature (and other categories). Then, it was worth $50,000, and I remember a number of loud voices, led by Odia Ofiemun and also included you, who had objections to the Prize on a number of issues. They even advocated boycotting it. How many of those issues have been sufficiently addressed as at today, and how do you rate the Prize as a now stable part of the Nigerian literary environment?

The NLNG started with $20,000.00 in prize money but the harsh criticism that met it from people like Odia Ofeimun and I came from a number of pertinent observations. Odia Ofeimun thought it was simply wrong to exclude Nigerians in the diaspora. It would make the prize a ghetto prize. Happily, that has been redressed now and all Nigerians can now enter for the prize. My main grouse with the prize was the non-disclosure of the identities of the judges. It didn’t help the prize at all that no one knew, at the time, who the judges were. This too, has been addressed and I think it adds significant cultural capital to the prize to know that knowledgeable people who also practised the craft are now in charge of adjudicating the prize. Overall, the administration of the prize has seen significant improvement, in my view. There is more attention paid to the quality of adjudication. Now there is a non-Nigerian judge as well. From initial hostility to the prize, more writers are now open to entering their works and that is a good thing.

Many critics of the Prize have spoken about the non-involvement of the organizers in publicizing the books on the shortlist, making them available in libraries and bookstores, and generally getting them into the hands of the reader before the announcement of the winner. Writer Ikhide Ikheloa is the loudest of these, who insisted that if NLNG would spend up this amount of money every year as a contribution to literature, they should also do more to get books across to the reading public. Do you share the view, or do you place the blame on the publishers/authors instead?

The book value-chain in Nigeria is distressed. Imagine for a moment that local government libraries existed, that state libraries took books into accession and that the Federal Library did the same. Imagine that university libraries actually purchased books. Publishers will not have to suffer as much. Authors will not go without royalties. One company alone cannot do these things. Publishers, the ministries of culture and the ministries of education must find a way out of this. A book that makes the long list of a prize as big as the NLNG ought to be in bookshops already.

Poetry is one of the less-celebrated (and less money-making) genres, perhaps because of its exclusive and reclusive nature. Do you care about this distance of poetry works in Nigeria today from the reading public?

I am glad you asked this question because it allows me to address the laziness of newspapers in Nigeria when it comes to serious literary culture. Worldwide, poetry is considered arcane but newspapers, magazines and supplements make it a vital part of the cultural landscape. Next, now defunct, tried to do this. Why aren’t more newspapers engaging our literature seriously? Poetry will never be as popular as prose but those who know will tell you that literature isn’t about popularity, it is about substance. Nigerian poets are way ahead of writers of Nigerian fiction. Consider that major poets like Chiedu Ezeanah did not even enter for the NLNG prize, consider that Niran Okewole did not enter and these are serious talents in themselves.

What role do you see for poetry in Nigeria, and in what space do you think your work occupies in the realm of things, and in this present generation?

Poetry’s role in Nigeria is, and will be poetry’s role the world over. It is our window into individual and collective consciousness, our expression of deep play, the most literary space for imagination, the last hope of the nation. Only the readers, the critics can tell what place my work will occupy in the scheme of things. I am happy that members of the generations before my own and some members of my generation and younger people have started responding critically to the work. One cannot wish for more.

Here is a question I ask almost everyone: what is your opinion on literature in indigenous languages. I won’t ask you why you don’t write in it, but I’ll ask what you think the future holds for that kind of writing.

There are prospects for literature originally written in indigenous languages and even for works translated into indigenous languages. Cultural politics and circuits of value originating especially from Africa and Asia lead inexorably to that conclusion. I write in Yoruba, my mother tongue. As a matter of fact I won the Delphic Laurel in poetry in 2009 for a poem in Yoruba. I am currently translating two Fagunwa novels into Yoruba. Work is going on all the time. A couple of years back my father translated Shakespeare’s play, ‘A Winter’s Tale’ into Yoruba and last year it was performed at the Shakespeare Globe by Wole Oguntokun’s Renegade Company to a packed, ecstatic Globe. 70% of the audience at every performance of the play were Yoruba people in Diaspora.

Have you read the work by the other two shortlisted writers (Amu Nnadi and Ogochukwu Promise)? What is your opinion on them?

Have you read the work by the other two shortlisted writers (Amu Nnadi and Ogochukwu Promise)? What is your opinion on them?

I am reading Amu Nnadi’s book presently. I haven’t finished. I do not have Wild Letters by Promise Ogochukwu. So far, I find the control of language and the very subtle imagery in Nnadi’s work fascinating, I have nothing but admiration for Nnadi’s craft. I have read all of Afam Akeh’s latest, it is simply breathtaking. A feat, actually, as well as a feast. I wish I could write like that. Indeed I took an epigraph from Letter Home for my own work, The Sahara Testaments and I am glad Afam Akeh himself likes my work.

Since you mentioned Afam Akeh, are there any other writers on the longlist that you expected on the shortlist but who didn’t make it?

The decision as to what works make what grades must be left to the judges who have had to read all the works submitted closely. Really, I can only speak of poets whose works I have read on the long list. I thought Amatoritsero Ede’s work and Gebinyo Ogbowei’s were singular, spectacular performances. Iquo Eke’s book surprised me. But those were the ones I read. I have not read the others.

As the president of PEN Nigeria, what has been your most memorable experience in writer advocacy?

Earlier this year, PEN Nigeria participated in the peer review process for observance of Human Rights in Nigeria. Our core competence is in Freedom of Expression and allied issues. The report is being discussed in the UN as we speak. Also, I was able to recommend a few Nigerian writers for sponsored visits to Sweden to discuss open society initiatives. But I think the case of Kayode Adeyemo & Another v. Extension Publications Limited, a case in which authors are challenging their own publisher for institutional piracy and copyright violation has to be the one I am most proud of as it breaks new grounds in our law and is showing other writers what to do about greedy publishers.

The Ghanaian poet Kofi Awonoor recently passed in a gruesome terrorist attack in Kenya. How do you respond to that as a poet, African, and the president of a writer advocacy group?

It was, awful, just awful, to lose Kofi Awoonor this way. I wrote a short tribute to Awoonor in Nigerian Tribune of Sunday 29th September 2013. PAN, the continental association of national PEN Centres is fashioning a robust response to this threat as we speak.

Where do you see African poetry (or poetry from Africa) two to three decades from now?

Poetry from Africans will always maintain its distinct character. From the time of Tchicaya U Tamsi, the poet that even our Okigbo conceded the laureateship till the present, we have not lacked exemplars who are engaging the continent and the world at large with remarkable success. In South Africa you can see poets like Rampolokeng, West Africa has produced Lamine Sol, Egypt has yielded poets like Gihan Omar and the Maghreb is well represented by poets like Samira Negrouche. There is no point of the compass, really, at which African poets are not re-inventing the craft and in many diverse languages too.

End.

_________

Kola Tubosun, editor of the NTLitMag can be found on twitter at @baroka.