Let’s begin with the space, for he was a man of immense spatial presence. Big, tall and fearfully dark, he occupied space like he owned it. Language was the first space he appropriated: the text of his creation, his creativity. Then there was his court, his physical space- a sort of loft really, linked to the main upstairs residential stretch by two flights of stairs. Children and women called this place ‘Abata’- a court, literally; his friends, the other poets in his Amunludun group, who were usually older than him, called it the studio. Sparsely furnished for a man of his reputation – but then space was the most important demand in his professional and social life, as there was no way children and observers of mock or serious performances in this hall would be denied their leg-room because of appurtenances.

At this time of my recall, circa ’85, I myself barely understood the huge dimension of creativity going on in that ‘upper parlor’. I noticed all kinds of humanity in never-ending traffic in and out- the political players, cultural researchers, high chiefs of all hues, journalists. I noticed the hunters and masqueraders especially, because of the way they bantered words gamely in their discourse of abuse. They would pose for verbal battle downstairs looking up at him in mock deviance, and he, dangling on his verandah like some kind of god, would riposte:’ Black- as- a- goat’, beginning with his own self abuse, ‘ I, the-first –eye-got-cruel-and-killed- the second, son of Foyanmun’. He had anticipated his enemy-chanter’s ace (for he was an intensely dark man, with a bad eye) he then pounced on them in verbal fisticuffs.

At this time of my recall, circa ’85, I myself barely understood the huge dimension of creativity going on in that ‘upper parlor’. I noticed all kinds of humanity in never-ending traffic in and out- the political players, cultural researchers, high chiefs of all hues, journalists. I noticed the hunters and masqueraders especially, because of the way they bantered words gamely in their discourse of abuse. They would pose for verbal battle downstairs looking up at him in mock deviance, and he, dangling on his verandah like some kind of god, would riposte:’ Black- as- a- goat’, beginning with his own self abuse, ‘ I, the-first –eye-got-cruel-and-killed- the second, son of Foyanmun’. He had anticipated his enemy-chanter’s ace (for he was an intensely dark man, with a bad eye) he then pounced on them in verbal fisticuffs.

His art was his gift- to the world and to his community; and when it was sought or discovered by his audience as his gift to them, the world became better for all concerned. The gift of language conjoined with the great gift of ethical perception in him, and wisdom ensued. He was always bare-chest on his verandah where he held court when he was not rehearsing with his group, a wrapper covering his torso. It was an ombudsman of sorts, with people all over the place bringing domestic upheavals for easy resolution, with words. He owned the language to persuade and to rebuff; to lampoon or to rhapsodise.

Oriki was his forte, so was public discourse. In fact, he was known as an inveterate public commentator- a practice that would deal the first devastating blow on his life and art, from which he never quite recovered. He had dared raise a reprimanding comment on his king and greatest patron- Soun of Ogbomoso- who usually invited him to entertain his publics and visitors and, who then was involved in a war of attrition with some of his high-chiefs, over paramountcy. As if that was not bad enough, he had to do it in the presence of a visiting military governor, who could determine the eventuality of the ruler-ship tussle. He was banned from performing in public and by the time the ban was lifted, Fuji and Juju had upstaged the allure of more traditional performances in public taste.

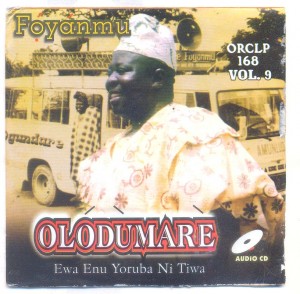

On Saturday 13th October 2012, Ogundare Foyanmun, one of the most gifted Yoruba verbal artistes departed this world at the age of eighty. And today, I pay homage to the only poet I know, in the long and fecund history of Yoruba word-smithy, who had transgressed certain borders of defined teleologies, to appropriate a rarefied art- one not of his fathers’- without training or initiation, and gone ahead to recast and repurpose it, and in the process, came through a most peculiar and unprecedented identity reconstruction in Yoruba traditional lore.

He was born in a Sango worshiping family, in fact, in the household of a renowned Sango priest. He was named Sangodare at birth. He trained as a barber- Onigbajamo, before he was a farmer. He ended up becoming the greatest ‘modern’ performer of Ijala-poetry of the hunters’ guild, Ogun’s art- and one of the more known exemplars of Yoruba culture.

The transition by which a Sango devotee came to excel so much in an art form of a rival deity- Ogun, and make it a profession throughout his life, is without doubt an example of disruptive imagination at work, a visceral practice characteristic of the trickster. For those who know the precarious character of cultic territorialism and ancient rivalry between the devotees of Sango and Ogun, Ogundare would certainly be considered as having risked certain grisly consequence for not devoting his talent to ‘Sango Pipe’, the art of his lineage, instead of Ijala, the trade of the Ogun worshipers. That consequence nearly dawned, from what I gathered growing up around his big court, if not for certain seeming inbuilt liberalism and tolerance of the Yoruba traditional religion, and of course the humorous wiles of the man himself. Ogundare Foyanmun, like Hermes, stole the fire of creativity from a most unlikely source.

But he owned the Anvil.

He came through the borders of creativity with neither ‘systematic and prescribed sequence’ of training nor technical corpus of the initiated, but with a mysterious and astonishing genius. It was rumoured he came to Ijala knowledge through a long and troubling sequence of dreams he had when he was a boy. But what was not in doubt is his deep knowledge of Yoruba language, genealogies and histories dating back to pre Yoruba formations – a set of skills that would take an average verbal artiste almost an entire half of life time to learn. He possessed a prodigious memory, a quick wit and a mellifluous voice, three important attributes of a successful verbal artiste, according to Oludare Olajubu, the oral traditions scholar. Yet nobody knew how he came by these, since no one in the family had been a performer before, except his grandfather who could chant, like all men of his time. He had been known to reach back through centuries of ancestral cognomen to sing the praise of a person on merely hearing the person’s family name. And among the living and the dead of that tribe of verbal artistes that modern Yoruba culture has thrown up, he has got to be the best ‘performer’ of Yoruba Language and lore, pace his arch-rival from Ilorin, Odolaye Aremu.

Adieu Baba L’oke.

_________________________

Peter Akinlabi, writer and poet, writes in from Ilorin, Nigeria

I own a compilation of his, and did not know he was still living. My respects, and condolence!

A nice piece.

Oga Peter, this one is so touching, so moving. Ogundare, flow on, river of song.

[…] new issue of the LitMag features the work of Peter Akinlabi. It is a tribute to Chief Ogundare Foyanmu, his uncle: hunter, poet, chanter, artist, and Ogbomosho chieftain; and that of Benson Eluma, […]