By Hezekiah Shobiye

“All of these goes to show that the aim of an equitable and efficient health financing system has and will probably not be achieved.”

Welcome to Part 3 of this series on Paying for Health in Nigeria. The focus here is on the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) and its role in increasing access to needed healthcare and ensuring equitable distribution of healthcare costs. This is a continuation of the analysis on health financing systems in Nigeria started in Part 1 and Part 2.

The NHIS, after several attempts by the federal government was finally launched in 2005. It is a form of social health insurance (SHI) system, which means that people are guaranteed the provision of needed health services upon payment of a token contribution in advance and at regular intervals. The NHIS like every other SHI was created to protect every member of the population, most especially the poor from the financial risk of accessing healthcare, increase access to quality healthcare services, and ultimately achieve universal coverage by 2015.

But 7 years after its inception, what has become of the NHIS? Is it on track to achieving its goals? Let us examine its impact using 3 hallmarks of every SHI:

- Universal coverage

- Access to health services

- Financial protection.

1). Has the NHIS achieved universal coverage?

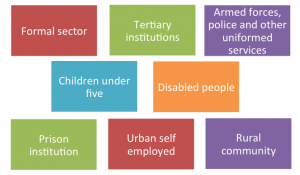

In order to achieve universal coverage, the scheme was designed to have 8 programmes addressing both the formal and informal sectors. This is shown in the diagram below:

However, only 3 out of these 8 programmes are currently in full operation – Formal sector, Maternal and child health project for pregnant women and children under 5 and the community based health insurance for the rural community. When the scheme kicked off in 2005, it began with the formal sector employees particularly the federal government employees. Participants register with an accredited Health Maintenance Organisation (HMO), which link them up with a number of service providers (clinics). Contributions are earning-related, with the employer paying 10% while the employees pay 5% of their basic salaries. This covers the employee, spouse and four children under the age of 18. Any child above the age of 18 is expected to be in the tertiary institution and will be covered under the tertiary institution programme. Each beneficiary is entitled to basic out- and in-patient care.

In 2008, the maternal and child health project (NHIS/MDG MCH Project) was also launched to provide free healthcare to pregnant women and children under 5 in 12 states of the country, while in 2009, the community based health insurance (CBHI) was approved by the federal government as the route to achieve universal coverage for the large chunk of the population in the rural areas. Although the total number of the CBHIs are unknown, the extent of their coverage nevertheless remains small. In all, only about 5 million Nigerians are enrolled in these 3 NHIS programmes. This amount represents just over 3% of the country with a population of 160 million people. While some have argued that this amount is a step in the right direction, majority have also questioned the feasibility of achieving universal coverage by 2015. The similarity between Nigeria’s struggle to attain the MDGs and the struggle to reach universal health insurance coverage cannot be overstated.

2). Has the NHIS improved access to quality healthcare?

As mentioned earlier, only 3% of the total population are currently insured under the NHIS – these are largely people living in the urban areas of the country where most of the health facilities are concentrated. Accessibility remains problematic in the rural areas where more than half of the population lives and where the healthcare need is more urgent. Majority of the HMOs are also reluctant to operate within these areas because of the lack of organised market structure and difficulty in collecting premiums. Even if they do, those who have access to the NHIS do not get the best treatment because of lack of adequate medical facilities and personnel in the rural areas. The uneven distribution of health facilities shows that this scheme provides more access to the richer population groups than to the poor.

3). Does the NHIS offer financial protection?

While the NHIS should be commended for the exemption of user fees for pregnant women and children under the NHIS/MDG MCH Project, it is important to state that this is just a minute fraction of the whole population. In addition, certain drugs and treatments of chronic illnesses such as cancer and diabetes are exempted from the benefit package of the scheme. This leaves patients at risk of still purchasing healthcare with their money. With over 70% living below $1 a day, there is still a high volume of households experiencing catastrophic spending. The argument here is always that these excluded treatments and drugs are very expensive, and if added onto the scheme, will drain the pooled funds in no time. If this argument is sustained, what are we going to say about a regular contributor who has not enjoyed any of the scheme’s benefits, suddenly develops one of these diseases like cancer but unable to receive treatment just because of an exclusion clause? This person, if poor will definitely not be able to afford the out-of-pocket payment for the treatment. Can the NHIS then be described to offer financial protection?

All of these goes to show that the aim of an equitable and efficient health financing system has and will probably not be achieved if the current trend continues. So what do you think is the way forward? Leave your comments below. I will also be giving my recommendations in the next edition.

[…] edition rounds up the series on ‘Paying for Health in Nigeria’. In Part 3, I concluded that the aim of an equitable and efficient health financing system has and will […]