“He who has gone, so we but cherish his memory, abides with us, more potent, nay, more present than the living man.” ~ Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

When I was 8 years old I watched a public execution on television. I am not exactly sure where my parents were or what they were doing at the time, or if the execution was real or created. I was the 4th of 4 children at the time and my much older siblings generally disliked me mainly because of my very lucrative blackmailing career. The three of them thought it necessary to get me to watch something terrible. Their threat of a repeat experience was a bargaining chip to lessen my terrorizing rule. I would not fully comprehend what I was watching but nevertheless I was enthralled. I watched as the men were tied to the huge drums and the horror of the gunshot and the wailing black maria will hold me captive for a very long time. It was a birth of a terrible phobia, one that has held me in its mesmerizing grip and has dictated my politics even in adulthood. I am registered as a Democrat in the US, mainly as a result of that party’s anti-capital punishment sentiment.

I heard about the nature of Ken Saro Wiwa’s death in my “political economy of natural resources” class at my small graduate school two years ago. I have always known about Ken Saro Wiwa and his movement and he had been my hero long before then, but I did not know the particulars of how he died. The teacher began the lecture and I was not surprised as my classmates turned to me as they inevitably do when “Africa” comes up. Unfortunately, on this occasion, I had not heard a thing about the way he died or the special horror it would invoke. I was deeply disturbed and I had to be excused from class that morning. A day later, I wrote my very first poem.

In 1950, Oil was discovered in the Niger Delta. The exploration that would lead to the birth and maturation of the largest scale environmental destruction started soon right after that. Years before the event that would cost him his life, in October 1941, Ken Saro Wiwa was born. He was the eldest son of Jim Wiwa, an Ogoni chief who lived in the city of Bori, now in Rivers State. Ken’s incredible brilliance would bring him to the halls of the University of Ibadan, where he would study English and excel among the greatest minds Nigeria has ever nurtured. After he graduated, he took up a post as a civil administrator for the major Niger Delta port of Bonny. His real education would start soon afterwards. Curiously, he supported the Nigerian government during the civil war and though he was opposed to the Biafran cause, he abhorred war above all. He wrote about this sentiment in two of his well-known works; Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English and a wartime diary called On a Darkling Plain.

Throughout his life, he would succeed in marrying the two opposite world of literature with that of business. In the 70s he built a successful real estate business and also became a grocer, selling vegetables and household items in the Niger Delta areas. His business empire was vast and so successful, that he was able to go back to his other love, literature. In the following decade, he would write poems and many books. He successfully documented the peculiarity of the Nigerian experience in one of his most popular works, Basi and Company, a satiric take on the Nigerian and his single-minded pursuit of wealth. The satiric soap opera became one of the most watched show in Nigeria’s history and as such in the whole of Africa.

He returned to the plight of his native Ogoniland in the beginning of the following decade. He joined other Ogoni elders to form MOSOP (Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People). He would not survive this. In the same year MOSOP released the Ogoni Bill of Rights, a work that declared the region’s independence. The document called for the Ogoni people’s autonomy and their right to manage the natural resources found on their land. They deplored the widespread pollution and damages done to them by the Nigerian government and other foreign actors. While MOSOP started as a grassroots effort, soon the movement would gain international legitimacy with Mr. Wiwa testifying in the summer of 1992 with the United Nations group on indigenous people. He spoke candidly about Shell’s human rights abuse, racist and genocidal policies against the Niger Delta and her people.

December of the same year, MOSOP released another document indicating that the organization will not back down regardless of all the manipulation and intimidation by the then military government and its allies. MOSOP continued to succeed, organizing one of the biggest protest rally with 300,000 people in attendance. An estimated 60% of the Ogoni population at the time came together to protest Shell and co’s destruction of their habitat and livelihood. The date, January 4th, will be known as Ogoni day henceforth. The struggle continued for Saro Wiwa and his leadership of MOSOP until May 21st 1994, the day things began to fall apart.

It is 21st of May 1994, the early morning sun brought with her soldiers and mobile policemen into Gokana, a city in the Niger Delta. The government forces were reported to have filed in with their weapons and tear gas. A MOSOP rally was to take place in the town that afternoon. As the sun rose in Gokana, and afternoon settled on the town, the crowd got so agitated that they brutally killed four Ogoni chiefs in a mad and bizarre rush. These men were known to be against the tactics of the leadership of the movement including Ken Saro Wiwa and were vocal about their dissent. He will be arrested along with many other leaders of the movement soon afterwards. The men were tortured, denied counsel and health care and were not allowed any contact with the outside world. They were finally charged with “incitement to murder” of the Ogoni four in January 1995.

Many of the prosecution’s witnesses would later recant their claims of Mr. Wiwa’s complicity in the murders. Two of them, Nayone Akpa and Charles Danwi would go as far as signing legal affidavit alluding to the fact that they were bribed and cajoled by Shell Corporation and her allies to testify against the defendants. Further evidence of Shell’s complicity in the wrongful execution of these men would present itself in the secret meeting held March 1995 between four senior officials of Shell and the leaders of the Nigerian Army and Nigerian police force. Owens Wiwa, Ken Saro Wiwa’s brother would later claim that an official of Shell by the last name of Anderson had asked him to stop the MOSOP protests in return for Ken’s life. The trial was heavily protested by all reasonable people in Nigeria and abroad.

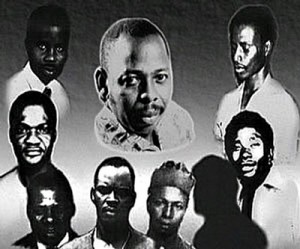

October 1995, Ken Saro Wiwa and 8 other members of MOSOP were sentenced to death by hanging and that was to be their fate. November 10 1999, 9 men were hanged for a crime they did not commit and one that the state could and did not prove.

Ken Saro Wiwa

Saturday Dobee

Nordu Gawo

Daniel Gbooko

Paul Levera

Felix Nuate

Baribor Bera

Barinem Krobel

John Kpuine

All these men were brutally murdered by a mad man leading a mad system with the express permission and support of Shell Corporation. Most account of this ordeal reports that Ken Saro Wiwa was the last man to die and he was forced to watch the other eight men as they were hanged. Even more chilling is the fact that they might have attempted to execute him multiple times.

Ken Saro Wiwa has been my hero for as long as I can remember. His life captured my attention since the day I heard about him. I am in awe of his passion and commitment to his people. His bravery in fighting, even though he predicted his death two years before, forces me to attempt to live a life of service and to not be afraid. His commitment to literature, the exacting world of satire, and his passion for business are all concepts I hope to emulate. He made money and art and to him there was no conflict. Today, November 10 2010 marks 15th anniversary of his death.

He was a man, he lived, and he died.

He read, and worked and loved and laughed. Those who knew him, remember him in laughter and they speak of his grand spirit that so captivated Ogoniland, the Nigerian people, and even his friend who executed him.

He was a man that stood for his principles. He hated war but he waged it against those who exploited his people. He was a peaceful man who died for a terrible crime he did not commit. He was a product of the best that there is in the Nigerian spirit and for that I have hope for our nation.

Today, I remember him and I cannot help but think that frequently in history, men such as Ken come among us to teach a particular lesson, and it is up to us to derive from them, the lesson that will illuminate our lives.

I really enjoyed your essay, it brought the day I first heard about the assassination in the news. Such a tragedy. Thank you for sharing.

[…] on the NigeriansTalk blog, Temie Giwa remembers Saro-Wiwa: Ken Saro Wiwa has been my hero for as long as I can remember… I am in […]

[…] dem Blog NigeriansTalk erinnert Temie Giwa so an Saro-Wiwa: Ken Saro Wiwa ist mein Held seit ich mich erinnern kann…. Ich habe Ehrfurcht […]

Hi, I found your article while reading up all I could find on the Martyr Ken-Saro Wiwa. Thanks for sharing, you may like to read what we did with his work ‘SozaBoy’ , http://tiny.cc/ookgyw . Thanks again.