He is the blacksmith of heaven, the one who molds the heads of new born babes. All the normal and special features of human beings used to be attributed to Ọbàtálá even though the special features came about by no fault of His.

When a mistake occurs, it may be that the mother refused to perform the necessary sacrifice. In some cases, the one truly responsible for the special features is the pregnant woman who steals a snail or violates taboo, say, by indulging in palm wine.

Nowadays, when a pregnant woman violates taboo: smokes cigarettes, uses Fansidar, Valium or Tetracycline in her first trimester, who do we hold responsible if the child is born with special features?

How can the outcomes of a mother’s ignorance or willful disobedience be the fault of Ọbàtálá? And should we ignore the interference of Iyámiàjé and Èsù? And there are barren women who are so impatient they insist that they must have a child, any child even if it is a thing, like Ọmọlókun who came to Agan Oribi.

Again, there is the place of Destiny (Àyànmǫ́), all those choices, spiritual, made by the individual and coded into that individual’s genes from the heavens which ultimately inform the course of the individual’s life. How are congenital features, which have been chosen by the individual’s Orí, the fault of Ǫbàtálá?

In one of the oríkìs of Òrìs̨ánlá there is a section that runs, ‘Arǫ̀run marinse lásán/torí abuké/torí aarǫ ni fi nlǫ’, which may be translated: he does not journey to the heavens for no reason/It is because of the hunchback/ and the cripple that he goes.

The cripple is special to Òrìs̨à. The hunchback is also important to Ǫbàtálá. Òrìs̨ánlá is their comfort, he is their solace. He sends them on errands, and people address them as Ęni Òrìs̨à, the close associates of the Òrìs̨à.

Our people also have an adage, ‘Orí àfín, onì oòrí Òòs̨à.’ You have seen albinos yet you claim you have never set eyes on Òrìs̨à. Is there anyone closer to Òrìs̨à than the albino?

Obàtárìs̨à, the King who wears white, the God-King, devotees appeal to Him for children, prosperity, to avenge wrongs they have suffered at the hands of others, to cure ailments and to heal deformities.

Ǫbàtálá is justly referred to as Alámǫ̀ rere, the excellent potter. Why do they continue to discriminate against the cripples, hunchbacks and albinos? Why do they continue to accuse the Òrìs̨à falsely? How so convenient, after they have pushed the ‘Other’ away they accuse the only One who accepts them unconditionally of being responsible for those conditions of ‘Otherness’ which they defined in the first place.

And this story about Òrìs̨à’s drunkenness at the time of creation is false. It is an old heresy. Ọbàtálá had given up palm wine by the time the Odú Òsá fùn-ún appeared, but Alákędun, a close servant of Òrìs̨ánlá, went bearing tales about Ọbàtálá, that Òrìs̨ánlá had been unable to overcome an addiction to palm wine.

What Alákędun did not know was that Òrìs̨ánlá was just using his gourd to carry oriri, in place of the quondam palm wine. When Alákędun saw that it was white stuff that issued from the lips of the gourd, he rushed to tell on Òrìs̨à. But when the other saints tasted the white stuff, it turned out to be ę̀kǫ, corn pap.

Alákędun says, O sa fùn-ún/o fun fun bi ęmu.

Ọbàtálá cursed Alákędun and he became an animal that lives in trees. Alákędun is the colobus monkey.†

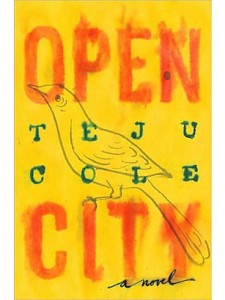

Part of my first reaction to Open City was, ‘I can relate to Julius’s lifestyle and his openness to all of life around him while being at the same time very selective. I can relate to him being so private. I can relate to feeling noble for having such sharp reflexes and responding in a timely manner to protect a mother and her baby. I can relate to some of his past, even the dumping of the files of his crime from his memory. I went to a boarding school where I had a moment of uncharacteristic, I think, callousness of which I had to be reminded and for which, in spite of my inability to recall the facts of the incident, I sincerely apologized years later. In my case, I had meted out corporal punishment.

Part of my first reaction to Open City was, ‘I can relate to Julius’s lifestyle and his openness to all of life around him while being at the same time very selective. I can relate to him being so private. I can relate to feeling noble for having such sharp reflexes and responding in a timely manner to protect a mother and her baby. I can relate to some of his past, even the dumping of the files of his crime from his memory. I went to a boarding school where I had a moment of uncharacteristic, I think, callousness of which I had to be reminded and for which, in spite of my inability to recall the facts of the incident, I sincerely apologized years later. In my case, I had meted out corporal punishment.

There are so many glimpses of myself that I catch in the revolving doors of Open City. And even more than the book’s author, it seems I have embraced Julius unconditionally. Cole is always being pressed in public appearances to show where Teju ends and Julius begins. As part of Cole’s defense mechanism, he seems, now, to have established some distance from Julius. Although, with some discerning audiences he embraces his alter ego, but it is never full, the embrace, further and delightfully complicating the relationship between fact and fiction.

For me, Open City is one of the finest works of realism I have read in a long time. In fact, in framing my first written response to the book, I chose to set Open City up in that great hall of contemporary realism, with novels like White Teeth, Elizabeth Costello. Open City, for me, is like life walked on to the pages of a book. Open City is as arresting as that lithograph made by M.C. Escher in which the Reptile[s] dissolves into the page and emerges from it again and again, in an endless cycle.

Another way to explain my disposition to Open City is to point out that I don’t trust myself, and when I’m offered such a convincing image of ‘me’, the image cannot be spared the relentless scrutiny and criticism to which my many selves are always subjected. But, it may be necessary to go into some more detail about the different ways my reflections have caught me as I passed by the glass that is Open City.

Let me begin by quoting Cole himself, from his Eight Letters to a Young Writer, ‘Don’t wait; write! Describe, describe, describe, and find the pleasure in pinning the right words to life’s incessant stream of sensations.’ I think Cole heeds his own advice, or that naturally would be his advice because of his predilections. Is it the chicken or the egg? Cole excels and I feel compelled to understand why this is so. Could it be that Cole has turned to good use his practice as an art historian and a photographer? These, generally, are professionals (or hobbyists) whose habitual practice it is to elevate the mundane with language.

However, I find Cole quite tame in terms of what I like to call ‘stylistic madness.’ Compared to, say, Roy’s The God of Small Things or Grass’s The Dog Years (even in translation The Dog Years is such Free Madness, à la Terry G!). Cole is content to be ‘poetic’, and that works well for the meditative tone of the novel. The ‘lyrical’ in Ms. Smith’s Lyrical Realism? Perhaps, beyond 9/11 this underscores the comparison, made by some, of Open City to Netherland and of Cole to O’Neill.

Anyway, what is more interesting is that Cole himself, in talking about his future projects, says we cannot continue to write novels as if Ulysses (and by extension Finnegan’s Wake) didn’t happen. For me, ‘plotlessness’ does not exist; the plot immediately exists with the form, the novel; it may be excellent, it may be trite, convoluted, loose, tortured or fragmentary but every novel has a ‘certain magnitude’, to modify Aristotle slightly. Indeed, the trajectory of a life is plot enough, so much for getting away from plot by traipsing cities. And speaking of cities, I am hoping someone would, one of these days, compare Teju Cole to China Miéville as both writers claim to be fascinated by ‘cityness.’

However, there is this flatness to the tales in Open City, and I am immediately moved to compare Open City to Mark Slouka’s The Visible World as a minor masterpiece that deals with some of the very same themes as Open City. In fact, the two gentlemen happen to sing in the same key, that poetic, meditative tone. The only difference, as I see it, is that Slouka is a masterful narrator. Cole seems yet to master not only plotting but of micro-plotting as well.

For now and on a personal scale of preference, I would rather read an essay by Cole, say ‘Fame, Obscurity and Poverty: The Art of Rembrandt and Vermeer’, I would rather read that than read a novel. It seems to me that Cole hasn’t entirely shaken his training in the Arts, and the advantages Cole’s practice gives may not be sufficient after all. Rembrandt and Vermeer are not exactly Cole’s area of expertise, but beyond the petty academic gerrymandering and professional turf wars, novels are an altogether different kind of animal, really. The proper course to follow, in this world of men, may be to do Dubliners and The Portrait, proving one knows how to properly treat a ball of yarn before one goes on to do Ulysses and Finnegan’s Wake, which are the diptychs of the world to come. However, if one considers that varying the move order is sometimes a way to find brilliant combinations, in Chess, one may be willing to grant that the same strategy might work for a writing career, too.

In addition to employing a 1st person point of view, Cole gives a lot of space to a description of things, ideas and less to narrating, and it is by playing to his strength that I believe he skirts some of the pitfalls that would have made Open City a poor book. In fact, Open City would have read like an overdose of Segun Afolabi, a writer I could not seem to bring myself to read as much as I intend to. Alienation. Even some of the distance that comes with Julius’s character can be explained away by suggesting that his professional practice as a psychiatrist has become second nature. Neat. I guess that Cole is quite aware of his own weaknesses as a narrator. He also seems to me very clever to have chosen to write in the first person, which helps to downplay this weakness. One is put in the difficult position of having to determine which are the actual failings in the narrative or what ought to be properly understood as the shortcomings of the fictional character-narrator.

Those failures in the narrative(s) that is Open City are made all the more excruciating by the brilliance of the descriptions. And this, to my mind, is linked to Benson Eluma’s observation that the book ‘is suffused with only one atmosphere from beginning to end, a reflective, intellectual atmosphere….’.

With the constancy of a metronome, we forgo the variations that are the essence of the polyrhythmic. But they are not mutually exclusive, constancy and polyrhythm. Why does Cole not combine two or more metronomes, or percussive instruments, each metronome being itself constant but creating variations by its interactions with the other percussive instruments? And this could have been applied to the narrative on any of so many levels. For instance, why one main narrator instead of two or three, as in Ulysses? Does anyone dispute the brilliance of Nas’s ‘NY State of Mind’? Yet, Black Star’s ‘Respiration’ is another level of sublime.

Or, at another level, I wonder why Cole didn’t combine two, three metronomes so that the waveforms they create interact in fascinating ways, with varying phase shifts, as the negative space of the one waveform gets filled, in so many ways, by the positive space of the other waveforms, producing a richer texture and colour and surprises. I seek to develop the discussion of Deleuze in Open City, that one which Cole merely adumbrates and which, tantalizing as it is, the auteur determines would be abruptly left underdeveloped. How is Open City a multiplicity, a rhizome, such that any point can be connected to anything else? There’s so much of the tree about the book, a heightened awareness of the distinction between the subject and objects.

Or, to introduce a visual metaphor in place of the aural I have largely relied on so far, is it that inside our minds it is all grey, monochromatic? And since Julius is inside his head for the most part, what one gets is just the high fidelity to reality that Cole manages to capture in the book. But that monochrome may be some construct foisted on us, as part of delineating the ‘I’, marking off the ‘inside’ from ‘outside’, but there is no such opposition. We are at once inside and outside, and the colours, they are endlessly refracted. Do we know which is the real and which the image? Are they all images? Are they all real but some are realer than others are? Cole, it seems, has succeeded in setting up a phenomenological experiment. It is left for me to consider what Cartesian variables to test. Did Descartes’s cogitation apprehend any verities?

In spite of all these, the realism succeeds, and the one thing which shines through is the genuine unreliability of Julius. For instance, when he begins to talk about Brewster’s paintings, he says the world of the paintings are hermetically sealed off from viewers, but he ends by saying he fell into the world of those paintings: very contradictory, very human, very realistic; we begin self-assuredly and are unapologetic in revising ourselves.

Or, to consider his retelling of that trip that took his family to the palaces of the Ooni and the Deji, Ikogosi and the Olumo rock, all in one day, such a trip is, erm, plausible. But the order in which Julius recalls the points of interest on that trip gives one cause to ingest the information he provides with a pinch of salt. That book really could have benefited from an editor who knows the cities and roads of South-Western Nigeria. Like Dami Ajayi observed, it would still have served the same purpose, plot-wise, if the family had visited just the Olumo.

Another shocking instance of Julius’s unreliability is his telling of the ominous event of his forgetting his ATM PIN. I initially mistook the incident as a foreshadowing of a serious amnesia, which made me begin to dread a particular kind of tragic ending that would not actually be similar but no less tragic than the story of Oliver Sacks’s Jimmie G. In the end, what is mind-numbing is a different kind of forgetfulness and a heightening of unreliability. We hear only indirectly from Julius the dark secret of a character failing. Violence is salient. I don’t think the fact of his crime is the most important item in his confessional reflections, although the violence may skew one’s reception and weighting. It is important, but no more than his estrangement from his mother but definitely more important than his understanding of the life and music of Mahler.

I’m a bit of a Mahler fan (yes, in the same way I am a bit of a Man. United fan). Julius’s fondness for Mahler however is not something I connect with, which is quite strange since that should have been common ground, but even that is no less discordant a note than his indifference to Jazz of which I am very fond. I will return to my take on Julius, Mahler and Jazz later. But, maybe Julius didn’t see it that way, his crime. There is a careless callousness of drunken young men, their obliviousness to the greater ramification of ‘mindless’ violence. Maybe, it was just another teenage conquest, easily erased, not so much as leaving a telltale trace on the ‘palimpsest’ of the memory. In fact, Julius dedicates some effort to suggesting that the lady had had a crush on him when he finally ‘deigns’ to remember who she is. Perhaps, he knew all along. This is the zenith of his unreliability.

If one’s thoughts crystallize when one is being mugged, I guess that would qualify as presence of mind. It would even be more beautiful if one gets mugged when one is drunk. Now, that would be some moment of clarity! That would be nirvana, similar, in more ways than one, to that famed near-death experience when all of one’s life flashes before one’s eyes in a moment. But nothing alters the fact that Julius is as pretentious as they come. However, it is that same quality that makes him a likable character, on the pages of a book. In real life, he would be one insufferable, uppity nigger—rehash of concert hall programmes trying to pass for insight into the art of Mahler? Nigger pleeez! The Real McCoy, a live one, like Dr. Akin Adesokan, would simply say: try listening to Bartok’s ‘The Miraculous Mandarin’ while reading Tutuola or Marquez. Yes, that is some insight, a real koan, novices like me could mull over that for centuries yet won’t exhaust all the facets of the jewel. And you know, that other flâneur, the real world Nassim Taleb, said, as quoted by Malcolm Gladwell, ‘Mahler is bad for volatility.’

There’s an old piece of Gladwell’s, probably written long before Taleb published The Black Swan, before Taleb became ‘the’ public intellectual. I believe the piece is online, somewhere, but I suspect it made it into Gladwell’s own What the Dog Saw but I am not sure. The context was Gladwell doing his thing to the world of Derivatives in Finance, so he set up a kind of a-day-in-the-life interview of a typical Hedge Fund manager with Taleb as that Hedge Fund manager.

One gets the sense from that piece that among the Quants in the building that housed Taleb’s office, Mahler was the hip composer to be ‘into’ but that Taleb himself, being the contrarian that he is, was a Baroque man. In Taleb, the real-world public intellectual portrayed by Gladwell in that piece, one could see, in an intimate way, the continuous refraction of art within the prism of a lived life. Unlike with Julius where one gets a lot of this Mahler, victim of anti-Semitism, but nothing of that other punctilious, slave-driving Mahler who not only drove his musicians to distraction but drove them up the wall as well. It is all romantic, too romantic, a fitting treatment for the bridge between the Romantic Movement and the Modern one. No earthiness to that handling of the maestro of Song of the Earth. No blood, no bile.

With Julius, what one expects to be emotional insights related directly to experience and the visceral has been replaced or emerges distorted by an overly studied apperception that travels the neural pathways in a direction opposite to that which one has come to accept as the normal course of affective response. Instead, the stream of perceptions seems to, largely, be a unidirectional flow of consciousness that takes it source from the headwaters of an all-knowing, all-apprehending homo sapiens.

The pull of power that attends the interplay of strong currents and their counter currents, the power impressed by the great turbulence, a turbulence which resolves, without any abatement in the power, into a single yet complex undertow is in Julius’s relations to people marked by its absence. One has long come to believe in a sort of synthesis of Empiricism and Idealism, to instinctively go beyond the opposition and accept, as the given, a dynamic equilibrium between two antagonistic views, but Julius seems to hark back to an earlier stage in the development of ideas, embodying the atavism of uninflected Idealism. This is not to say there aren’t instances and examples in Julius’s account that can be construed as contradictory to the summation of his character I’ve just provided. Yet, for me, the overall impression hangs heavy and will not budge even to contradictory particulars.

If I’ve any doubt in my mind that Julius is autistic, that he seems, most times, unable to connect with people, that he transmits the tales told him by others too blandly, the fact which removes my uncertainty is that a ‘weirdo’ psychiatrist who’s into Mahler doesn’t flirt with the idea of a Mahler who suffered from Asperger’s syndrome, not even to marshal strong historical arguments against it or to even dismiss it as one would flick a hand, distractedly. On the strength of Autism alone, a real-fictive, probably ahistorical but all the more engaging, Mahler would have emerged. Now, I must acknowledge that the path of my conjecture about Julius’s autism is a convoluted, one which intersects itself at numerous points.

But there’s something else that is striking here. There’s a real, historical personage who was also German, an émigré, who also waxed eloquent about Mahler, reflected on anti-semitism, and said some of the most atrocious things about Jazz—Theodor Adorno. Some of the meta-critiques of Adorno’s critique of Jazz have attempted to show that Adorno by being overly formalistic in his approach to Jazz could not have found in the form alone the justifications for claims that were made for the culture based not only on its history and the reception of the music by its audience but also on the methods of its production the political milieu and lifestyles of its exponents.

I have interpreted these critiques to mean that there was much Adorno missed by adopting the restricted methods of enquiry of a musicologist of Western musical forms. Supplemented with the methods of a Marxist sociologist, as that methodology must have been, Adorno’s writings on Jazz are still shot through with inaccuracies. His smug expression of outrage—at the ‘fraud’ of a recipe which he copied from the glossy magazine, ‘Jasm, and which he claims led him to expect a sumptuous repast—seems unwilling to admit that his hopes were hinged on the very lean gleanings in his own pantry and that if there’s some other factor deserving of blame, it may be the deficiencies of his own culinary skills. He would have been better served if he attempted, instead, a social history and ethnography of a ‘popular’ music.

Adorno, it seems, treated Jazz more as one would a genre of music rather than as a culture. Of course, he addressed himself to the Culture but those are largely inductions made on the basis of what Adorno read within the form and also on deductions from his overarching philosophical framework. And, although Julius never gives up his role of the outsider looking in, in relation to Jazz, he seems to develop a more respectful disposition from afar. We are not told that the friend who promised to show him how the form works ever does so. Perhaps, in the end, the transformation, the parting of the heavens, may rely less on an understanding of blue and swung notes and more on access to the music of Jazzmen through their lived lives.

Julius is introduced, vicariously, to the life of one of Jazz’s greatest exponents. That was Cannonball, who—coincidentally?—belonged to a generation of Jazzmen who developed a new kind of Jazz that responded to some of Adorno’s formal criticisms whether consciously or just in the natural course of developing their art form without even as much as a sideways glance in the direction of the distraught critic. The cloying, ambient music to which Julius alludes is suggestive of the styles that were predominant at the time when Adorno’s first critiques of Jazz were published; they definitely were not music from Kind of Blue or even the bop era. And since I am on the issue of the generation of Jazzmen who developed a new kind of Jazz that responded to some of Adorno’s criticisms, there is also the influence of those other gentleman, like Ornette Coleman, whose free jazz differed from the innovations of Miles Davis (who followed George Russell). Of course, Cannonball was Davis’s sideman on the epochal Kind of Blue.

All these seem to suggest that Julius stands for Adorno, in the position of a penitent. I accept even his initial, mild indifference as sufficient apology for Adorno’s dismissal. And they say Adorno had it in for America. It is interesting that Julius, in remarking on his indifference, describes Jazz as that most ‘American’ of musical styles. Even the word ‘form’, as in ‘most American of musical forms’, is eschewed in favour of a more conciliatory ‘style.’

Now, name checking a phat cat like Walter Benjamin, that fine feline, is bound to drag in not only Adorno but Marcuse as well. And for me, Julius, as a type of the intellectual, is a one-dimensional man. Sometimes, when intellectuals are engaged in discussions and stray into unfamiliar territory they resort to all sorts of stratagems; by ‘name checking’ I’m not saying Cole doesn’t know all the stuff to which he alludes, but my quarrel is with this pretentious Julius even though he only name checks Benjamin indirectly, through our friend, the reluctant fundamentalist. The way in which Julius differs from the specimen of Marcuse’s classic critique, in the strict sense, is that Julius’s condition, to my mind, is related to episteme, not the techne and technological society which Marcuse attacked. Of course, Julius is embedded in that technological society. Julius is alienated, and he strikes me, at times, as the embodiment of the very extremes of Descartes’s Cogito. Julius is/is not present, in the body or in language, to others. There’s a failure of (affective) language in his exchange with his girlfriend. He is seemingly not present in the body to the brothers who mug him.

It is as if Cole has set up a phenomenonlogical experiment in Julius. The ‘intentionality’ of Julius’s consciousness, that ‘tending toward’, that ‘pointing to’ is palpable. So is the compulsion to describe and describe, to describe whatever datum Julius is conscious of. It is as if when Julius, and I with him, tries to look into Julius’s consciousness, we only succeed in looking through it, in looking beyond it, like a piece of glass; a prism; a lens in an optical experiment, instrument; like an eye looking through itself; like the eye in this Age of Electronic Reproduction. Julius is Husserlian. And Husserl, of course, accepts, a priori, Descartes’s Cogito. That is the first move of Husserl’s Epoche. But, if this is so, does one not immediately begin to sense the presence of the ghost of Heiddeger on the back of one’s neck? A ghost that possibly rode in on the coat tails of Marcuse? Doesn’t the being of Julius beg a Heideggerian critique?

It is for these reasons and some others that do not come to mind right now that I prize Open City and find it endlessly fascinating.

___

†Ifáyęmí Ęlę́buìbǫn (1998) The Adventures of Ǫbàtálá (Part 2): Oríkìs by the Awìís̨e of Òs̨ogbo; Àrà Ifá Publishing; Lynwood; pp. 5-7, 112-115, 118-120

___

Adebiyi Olusolape is the Poetry editor of Saraba Magazine.

[…] short stories by Anja Choon and Olumide Abimbola, poetry by Benson Eluma and Kolade Ajayi, reviews by Adebiyi Olusolape, and a delightful non-fiction by Temie Giwa. All delightful, […]

[…] evening sessions at the Ibadan Poetry Club: lyrical, personal, and experimental. There is also a review of Teju Cole’s Open City in which Adebiyi Adesolape brings his lexical dexterity to bear on a task that demanded the depth […]