Jude Idada’s epic play challenge readers to reconsider history. It pries out lessons of good leadership, governance, social and moral values from narratives. It also urges us to interrogate history, and to disseminate historic stories and its values in the most artistic and enjoyable form.

Those familiar with language and culture of the Benin people will be able to infer great similarities shared between the Edos and the Yoruba. For anthropologists, it shows great indices of interaction, socio-political emergence and roots of the peoples in that cultural reality.

Those familiar with language and culture of the Benin people will be able to infer great similarities shared between the Edos and the Yoruba. For anthropologists, it shows great indices of interaction, socio-political emergence and roots of the peoples in that cultural reality.

Various scholars have taken account of the narratives of the progenitor of the Yoruba, Oduduwa. Some have leaned to the mythical narrative, which states that Oduduwa was a man who due to his excellent leadership became deified. Some say he came from the skies. Another historical point of view asserts that Oduduwa was the son of Lamurudu, a great man of potent magic and herbs evicted from Mecca during the Islamic Jihads. Jude Idada’s Oduduwa gives credence to the Benin narrative of the progenitor of Yorubaland, which takes perhaps one of the more critical and realistic narrative of the emergence of a great king in Yorubaland.

Oduduwa, King of the Edos revealed that Ekaladerhan, a young prince from the long line of the Ogiso dynasty was sentenced to death by his father. His fate was sealed but the sympathetic chief-beheader found a way to spare his life. He ran through the forests and made his way to an unknown settlement named Ile-Ife. There, he solved the problems of the people of Ile-Ife, organized them into a more profound unit, taught them artistic and economic skills, and became a powerful sorcerer and ruler. He was named Oduduwa by the people of Ile-Ife who worshipped him as their saviour and king.

The Ogiso dynasty ended in Benin Kingdom. Ekaladerhan’s father had passed on and there was no one to become King. A regent was appointed among the chiefs but this relatively co-leadership arrangement led to strife, as Evian, the regent tried to impose his son as an Ogiso.

The play opens with a civil war in Benin Kingdom between Evian, a regent who wanted to begin a new dynasty of kings from his root and his supporters on one hand, and the chiefs who wanted to continue the sacred lineage of the Ogiso dynasty – the Igodomigodo dynasty.

For a great kingdom to emerge, it cannot be ruled only by the symbols of a divine dynasty. The Benin chiefs were constantly embattled between retaining a long entrenched monarchy, creating a chaos of a republic or a parliamentary system of governance.

Ekaladerhan was sentenced to death for killing a pregnant woman. It was after he had been sentenced that the truth was revealed that he had been wrongfully accused. The Ogiso dynasty fell because of Ogiso Owodo, Ekaladerhan’s father’s high-handedness and the king was banished, left to live like a dog in the outskirts of the land.

One of the chiefs, Ezomo had kept a precious secret that could save the Benin people from continuous scuffle for the throne. He was long informed of a living Ogiso who was established as Oduduwa in Yorubaland. It then became the task of select chiefs to bring back their Ogiso or continue to live in a crisis of leadership.

A look at Chief Uwafiokun at this point is important. The character Uwafiokun is a warrior-chief who first hinted of the Edos’ disgust and age long hostility for the Yorubas, an issue they knew not much about at that point in history. Uwafiokun is also married to one of the Ogiso’s daughters. His hostile response to the search for a lost prince speaks volume of an ulterior motive.

Uwafiokun is also quick to anger and would rather use the sword than think of amicable ways to solve issues. He is brave and had helped to maintain the Ogiso dynasty’s hold on Benin Kingdom by killing regent Evian and his supporters. Like the play notes “it is not a man with sword that is called a warrior” (Page 47), other chiefs, Oliha and Ezomo had played far greater roles in solving the problems without lifting a sword. Uwafiokun is a dictator at heart, interesting schemer, through whom the reader is reminded of the history of military governance in Nigeria.

We have Chief Oliha, a man whom the writer imbues with an inverse David and Jonathan relationship. Oliha is a wise man; one who understands that not all those who pay homage to their nation and their culture, loves and hope to preserve it. Oliha was a companion of Prince Ekaladerhan, a trusted friend who was appointed to bring back Oduduwa to the throne of his fathers.

The major conflict of the work is the essential crisis of identity in culture. What is culture and how do we change it without incurring the wrath of the harbingers of culture? The book also presents argument for, and against monarchy, a clamour for republicanism, amongst others. The role of African women in shaping culture through their social and limited political roles is also examined.

Ivie, daughter of an Ogiso and wife of Uwafiokun presents a case for a new government based on the quality of character and not a monarchy, a form of democracy. She argues against the myth of the divine bloodline, but this will surely be against the cultural cooperation of the essential myths that keep the kingdom united. Her stance is further established if we consider that Oduduwa, a man in exile was made king by people of Ile-Ife. He performed greatly and was gifted the divine right by the people of Ile-Ife, because of his character and contributions. Unlike his father Ogiso Owodo, a tyrant king with all the divine right, who silenced the voices of chiefs and sentenced his son to death. Absolute monarchy may not be a culture of the Edos, they had cultural systems to banish Ogiso Owodo and they did.

However, Oranmiyan, son of Oduduwa, became the first Oba of Benin and greatly reduced the powers of the chiefs to mere ‘Yes’ men (Page 159). Oranmiyan forcefully changed cultural norms, challenged old cultures with absolute decrees, but left Edo land in anger because he did not win the legitimacy of kingship. He left in anger but entrenched the Ogiso bloodline by making his son, Owomika the Oba.

This brings me to the idea of home and exile and how the author subtly interrogates it from the responses of Oduduwa. Oduduwa had become a man in exile and also prosperous in a foreign land. He had taken up a new name and had assimilated the culture of the Yorubas with his knowledge of medicine, of military structuring and more. In one word, his exile made him contribute much more to his base than to his native land. Amidst the fact the Oliha troubles him with the good times of their youth and urges him to abandon the people of Ile-Ife. When the time to make this tough decision came, Oduduwa’s response is of gratefulness to the people of Ile-Ife for accommodating and elevating him. He asserts in the play, “where a man finds peace and tranquillity, he will call his own”. This is a question for scholars who are considering self-exiled men of knowledge in the Diaspora, and their contributions to the intellectual and socioeconomic development of their ‘new homes’ instead of their native land.

The play is well-researched with notes which made references to actual dates, places where these historical events occurred and where they are located in present day Edo State. This further entrenches the verisimilitude and the possibilities of some of these events.

There are potential points of departure and criticism that can be inferred from the work. Jude Idada’s Oduduwa subtly posits that many of the developments that have become profound historical, cultural and artistic identities and civilization of the Yorubas were exports from the Benin people. Also by my knowledge of Oduduwa, in Yoruba historical narrative; he had seven children who founded seven major kingdoms, but Idada shows that Oduduwa had 32 children – to create a possibility of royalty in a largely agrarian community. Idada takes into account existing Yoruba narratives about Oduduwa and explains its unreliability. As seen in this epic play, it was a transfer of market gossip entrenched in history that noted Oduduwa was the son of Lumurudu and the Yoruba myth that Oduduwa came from the sky, is largely a ploy by kings to rule others.

Idada also gave a brief insight on the reasons why none of the seven sons of Oduduwa became Ooni of Ife. The play notes that the Ooni was an adopted son of Oduduwa, a child whose mother was spared by the gods. By my knowledge, some historians have claimed that Ooni was one of the Ile-Ife chiefs, loyal to Oduduwa when he was venturing to assimilate the many hamlets that are now Ile-Ife. This is a matter for the historians to further prove or disprove.

The book, as expected of a truly African epic is filled with proverbs, songs, dirges, incantations and colourful but accessible language. The songs serve different roles in the play. At some point in the narrative, songs are used to express the possible turn of events, expressing the hopes and aspirations of the peoples and also to recall past events that have shaped the present circumstances. The songs also build the reader’s anticipation for characters that are making decisions that will shape the entire plot of the play. On page 74, the songs served as a tool for arguing between the Yoruba Nation and the Edo Nation, and later as a tool for reconciliation and celebration. Idada’s Oduduwa is filled with well-crafted ironical occurrences, performatives, individual and cultural levels of conflict, a picturesque set and a realistic narrative.

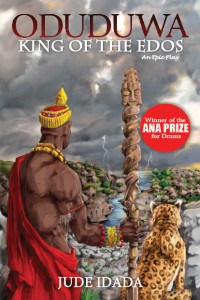

Jude Idada, a screen writer, filmmaker and dramatist, has published works in the three genres of literature. He won the 2013 Association of Nigerian Authors’ Prize for Drama with his play, Oduduwa: King of the Edos.

[…] REVIEW | Oduduwa: King of the Edos by Femi […]

[…] longlisted authors and their drama works include: Jude Idada’s Oduduwa, King of the Edos, John Friday Abba’s Alekwu Night Dance; Patrick Ogbe Adaofuyi’s Canterkerous […]

[…] Jude Idada’s Oduduwa: King of the Edos – A Review […]

I used to do this when I was a student. It’s called working to the answer….. You know the history of the Yorubas because it’s widely written about in recent years, and so you write your history to match it with Binis as the wise benefactor society.. Lol… Who next? The Portuguese were long lost Bini explorers who “returned home” white? Funny…

This is a joke. Oduduwa had absolutely nothing to do with the character this man describes. Later day revisionism by Edo. Jokers.